Remembering Minnette de Silva: the architect in a sari

As part of South Asian Heritage Month, Sumita Singha OBE explores the contributions made by Sri Lankan architect, Minnette de Silva, to the built environment and gender equality.

The reception of the 2023 Royal Gold Medal by Yasmeen Lari has shed much needed light on women architects from South Asia. There are many women pioneers from South Asia who have not been celebrated during their lifetimes. Sri Lanka’s Minette de Silva is one of these. She was the first Asian woman to become an associate of RIBA, the first woman architect from Sri Lanka, and only one of the two women in the world to lead her own practice in 1948.

Early life

Minnette de Silva’s life spanned between 1918 and 1998 with wars, travel, and economic upheavals. De Silva was born before the end of the Great War in British Ceylon (Sri Lanka now) - the youngest of five children. Her father, George de Silva, was a Buddhist Singhalese politician. Her mother, Agnes Nell, was a 'Burgher'- of Eurasian heritage; and a Christian.

Due to family issues, de Silva remained a peripatetic student, attending schools in Sri Lanka and the UK. The 1930s depression hit Sri Lanka when she returned from the UK, and she could not complete her schooling. A lack of money remained a problem throughout her life, but she was often able to persuade people to pay for her studies and travel.

Several factors propelled de Silva towards architecture including her mother’s interest in the arts and crafts, the influence of artists, such as the renowned Sri Lankan art historian, Ananda Coomaraswamy, family visits to Sri Lankan heritage sites, and in particular, meeting Oliver Weerasinghe, a town planner.

As de Silva had not finished formal schooling, she could not enrol to study architecture at the University but later this disadvantage would enable her life to take an international aspect. So de Silva worked as an apprentice at the Bombay (now Mumbai) firm of Mistri & Bhedwar, managing with just one free meal a day that the office provided to make ends meet. In the evenings, de Silva studied at a private architecture academy in Bombay from 1940 where she was the only woman in a class of 40. By now, the Second World War was raging.

During her visits home, de Silva attended the Technical College in Colombo. After finishing there, in 1943, she enrolled in the Government School of Architecture in Bombay but was expelled for attending a Quit India march and not apologising for it. Undeterred, she worked for seven months in Bangalore for German Jewish refugee, Otto Koenigsberger, the chief architect and town planner of Mysore, in 1944.

Around 1945, de Silva became one of the founders of an Asian focussed architectural journal, MARG (Modern Architectural Research Group) in Bombay along with her sister, the art historian, Marcia (Anil) de Silva. She was able to publish her writings in it, but de Silva also wanted to finish her architecture studies.

Thanks to a chance meeting with Herwald Ramsbotham, the Governor-General of Ceylon, who also happened to be the Parliamentary Secretary to the UK’s Board of Education, she was able to enrol at the Architectural Association. In the invitation letter from RIBA, she was instructed not to send her drawings in case they were lost due to ‘enemy action’- but she was able to find sponsorship for her travel to the UK by ship after the end of the war.

Architecture career

After passing the special RIBA examination for returning students over the age of 30, Minnette de Silva became an associate of RIBA in 1948. That year Sri Lanka became independent, and she returned to start her practice, Studio of Modern Architecture, from her parent’s home in Kandy. Her clients came from the newly emerging professional middle class of Sri Lanka.

Like her own ethnicity, de Silva’s architecture borrowed from Sri Lankan and Western contexts. Using modern materials such as concrete and rough finishes for light-filled and airy designs, along with ‘traditional’ materials such as earth and bamboo, handwoven textiles, lacquerware, brass; and wood carvings, her work was uniquely of the place. She was also able to help local artisans, particularly women, through her work and advocacy.

Her work in the 1950s was mostly housing - private and public. But in 1962, her mother to whom she was very attached died and this had a great impact on her. She began to find it increasingly difficult to get commissions in the 1970s. Perhaps to cope with her grief and the new political climate in Sri Lanka, she travelled a lot in the 1960s and 1970s to the detriment of her practice.

In 1973, de Silva stayed in London, from where she contributed the section on South Asian architecture in a new edition of Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture. On the back of this, she was invited to Hong Kong as a lecturer on Asian architecture. One of her students from Hong Kong recalled that she never spoke about her built work.

Returning to Sri Lanka aged 62, de Silva tried to revive her practice but three years later, the civil war broke out. With a handful of projects completed in that period, de Silva died aged 80 in 1998. Most of her 40 works have been demolished or altered and archives lost. Architects’ works are not immune to destruction, especially if they are not recognised like de Silva was- but thankfully her ideas and intentions remained and have had a lasting impact.

For instance, de Silva wrote about the kind of modern architecture that would suit poorer nations - socially, environmentally, and materially. She called it Modern Regionalist Architecture, which decades later came to be known as Critical Regionalism. Her work and writings are said to have influenced many architects and theorists from the subcontinent and beyond, including the better-known Geoffrey Bawa, who was a year younger in age but ten years behind her in practice.

An invisible struggle

For de Silva, there was another invisible struggle. In her home country, she remained an outsider due to her mixed heritage; while in the West, her beauty and clothes served to exoticise her. Despite spending long periods in the UK, she did not set up a practice there. Short of money, de Silva wore ‘cheap’ saris from Bombay, and instead of jewellery, wore flowers in her hair.

But this became an advantage as she was photographed, unfazed, surrounded by famous European men such as Picasso, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Le Corbusier and invited to speak to the Queen at the Royal Garden Party in 1948.

Lester James Peries even references the appeal of de Silva's appearance in his column 'The Eastern Eye' in The Times of Ceylon ( a daily newspaper in Sri Lanka), July 1948: "Was it all due to the picturesque saree...could it be the irresistible lure of the mysterious East?"

I was informed that there were only two images of her in RIBAPix - one being a painting of her and another, the iconic image featured above of her in Colombo from 1951, looking askance while clambering up wooden scaffolding in sari and chappals. But I looked further.

In a group photograph at the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) VI, in 1947 in Bridgwater, England, I spotted de Silva, resplendent in a sari with which she had created a head covering in the cold weather, the youngest and the only (and first) Asian delegate, sitting in the front row, between Sigfried Giedion and Walter Gropius. The caption originally did not include her but has now been updated following this research.

Facing misogyny in the built environment

De Silva’s decision to practise from the ‘backwaters’ of Kandy is cited as the reason for her lack of work, but essentially, de Silva was a woman in a man’s world - whether in her home country or outside it. Ahead of her time, de Silva’s ideas were popularised by men, but she was not credited properly. Just two years before her death, the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects awarded de Silva its SLIA Gold Medal - 14 years after it recognised Bawa.

Minnette de Silva was compared unflatteringly with men, but she was the one who took the risks. For instance, she ran her own practice from a small town while Bawa started off by taking over an existing practice from the capital city.

While the nature of de Silva’s friendship with Le Corbusier was brought up in books and lectures, Bawa’s close friendship with a self-confessed paedophile, Donald Friend, is hardly mentioned. Bawa poached de Silva’s employee, the Danish architect, Ulrik Plesner (who would mention de Silva scurrilously in his memoir, but not Bawa, even though he fell out with him). These hardships must have made her weary and possibly led to the further deterioration of her mental health.

The enduring legacy

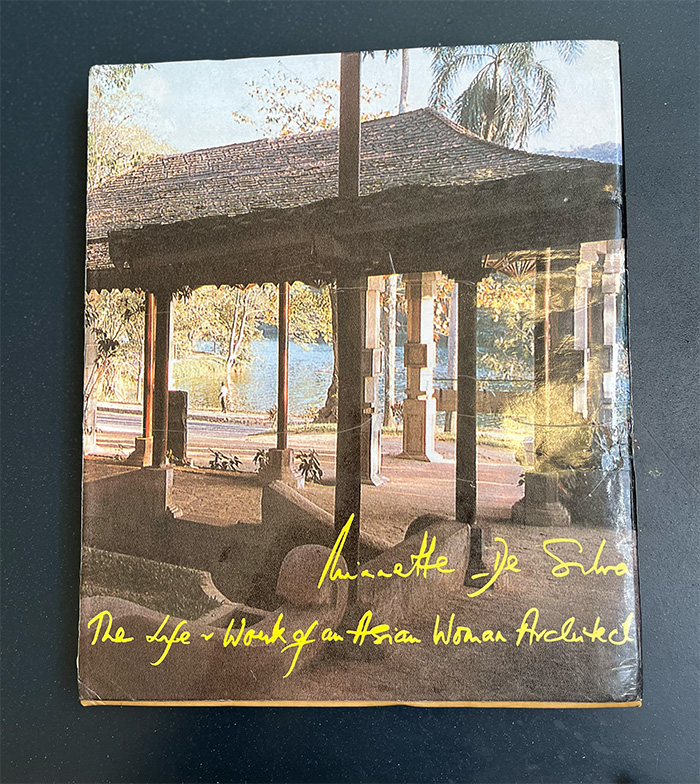

Minnette de Silva became increasingly erratic and eccentric towards the end of her life, obstructing any help to document her work. Instead, she wrote a charmingly illustrated ‘scrapbook’ autobiography, The Life and Works of an Asian Woman Architect. This unedited work was published after her death but the second part of this account has vanished.

In today’s climate and resource crisis, de Silva’s designs and her writings are particularly important. De Silva’s design methodology included participation and consultation- in this also she was years ahead. As Sri Lanka, and the world, struggles with economic crises and wars, Minnette de Silva’s designs using local materials and techniques, reducing building costs and energy use are of great significance. It is time to recognise the great architect that she was as well as salute her personal bravery as a woman striving to help others, despite her own problems. Her special ability to turn adversity into opportunity could inspire us all.

This article was written by Sumita Singha OBE as part of South Asian Heritage Month (18 July to 17 August).

Sumita is an award-winning architect, academic and author, who studied architecture in New Delhi and now works in the UK. She founded RIBA’s equality forum, Architects for Change and is the Trustee for RIBA and Commonwealth Association of Architects.

Additional thanks to British architect, Wendy de Silva, (no relation), who worked for Bawa, for her insights into the Sri Lankan architectural world.

For Minnette de Silva's life and work, see the blog post by David Robson - Andrew Boyd and Minnette de Silva: Two Pioneers of Modernism in Ceylon.

Learn more about RIBA’s equity, diversity, and inclusion work.