Alternative modernism: the architecture of China's people's commune

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng, Royal College of Art

Awards RIBA President's Awards for Research 2020

Category History and Theory

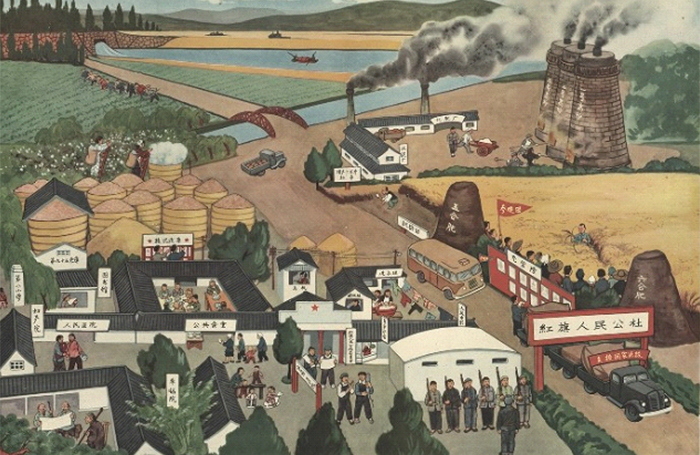

The people’s commune, an all-encompassing socio-political, economic and spatial model of China’s collectivisation during the 1950s-80s, played a fundamental role in the process of the then newly established nation-state to transform an agrarian economy into an industrialised socialist society. While synthesising the political economy and socio-cultural transformations of the commune system, this research aims to provide the first systematic account of the architecture of China’s people’s commune across scales of territory, settlement and housing. By employing an architectural case study method, the research revisits pilot commune proposals and exemplary propaganda posters, and, through multi-year fieldwork, has documented one of the few still existing commune settlements today, including oral histories with the then commune leaders and members. The architecture of the people’s commune articulated and enforced the construct of collective subjectivities. The coupling of public canteens with the abolishment of family kitchens formalised a practice of everyday life that aimed to collectivise the socio-economic functions of dwelling. The spatialisation of a systematic arrangement of social roles in household management, service provision and agricultural production destabilised social ties formed in the extended family and the patriarchal clan system. Instrumental to the restructuring of social relationships, architecture and planning are, in this sense, political disciplines. Revisiting the people’s commune is crucial, not only for a better, contextualised understanding of the social realities and spaces it has produced in relation to contemporary issues in China’s rural and urban transformations, but also for a critical examination of the core of China’s governmentality at its early formation: the correlation between the spatial, social and political units, particularly at the neighbourhood scale. Moreover, constitutive to the non-canonical architectural histories, the people’s commune challenges preconceptions of Western modernism that is based on the construct of the individual and the nuclear family and their relationships with the civil society.