Planning a town and a country in a hundred and eighty pages

Calvin Hin-Long Po, Architectural Association School of Architecture, UK

Awards RIBA President's Awards for Research 2021

Category History and Theory

Behind canons of post-WW2 architects and how they redefined England’s townscape, an invisible, parallel history made this possible: the legislative apparatus that made the state the final arbiter of all development. With recent governments questioning the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act’s legacies, this paper traces modern planning powers’ origins further to an embryonic moment: Uthwatt Committee’s Report (1942). This paper interrogates the Report’s role as an invisible ‘architect’ of the postwar English townscape

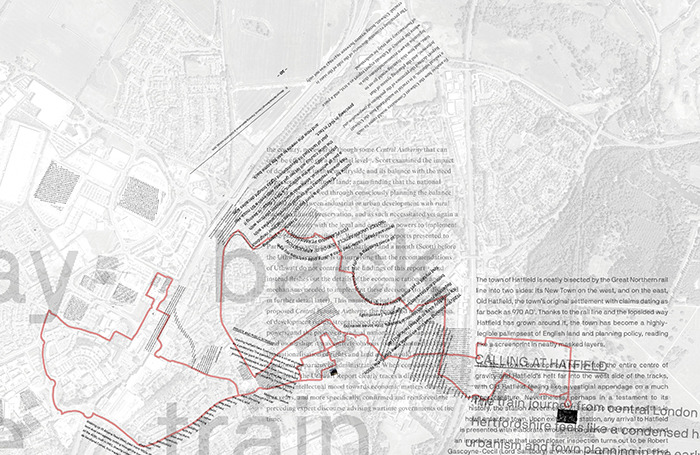

This paper interweaves two narratives: the Report’s analysis, and a walk through Hatfield, a peripatetic reading of the Report’s co-authorship over this Hertfordshire town.

Through analysing the Report’s text and context, this paper reveals how Uthwatt exceeded its original mandate to fix a technical planning mechanism (‘compensation and betterment’, i.e. land value taxation). This paper deconstructs Uthwatt’s arguments for radical solutions based on “total war” centralisation, post-Blitz urgency, failing laissez-faire markets, and post-Depression trends towards technocratic rationalism. It examines impacts of Uthwatt’s proposals: unprecedentedly extending planning controls nationwide, empowering compulsory purchase at capped prices, and critically, nationalising development rights of land. The latter fundamentally reformulated land ownership: from previously entitling landowners to develop land unless restricted by state, to having no rights to develop unless permitted. Even with today’s proposals for ‘first-principles’ planning reform, this remains the foundational legitimacy of all planning legislation since, demarcating the line where individual property rights end and public (or state’s) interest begins.

From wartime requisitioning of private (aristocratic) property in Hatfield House, suburban house extensions, to its New Town, Hatfield’s urban fabric becomes a palimpsest of the Report’s ideas, inscribed onto planning legislation, and onto England’s town and country. This paper elucidates power relationships between legislating/governing and architecture, bureaucratic text and architectural experience, both in this paper’s own text and its calligram-based typography, visualising textual interplay on this paper’s pages.