MMAS - Practice Role Model

Embracing complexity and instigating social change

Belfast has become a chronically disconnected city, littered with cul-de-sacs, vacant land and large-scale fences. As a result, you leave your front door to go about your day and instead of seeing some greenery or your neighbour, the first things you encounter are boundaries and enclosure.

We want our work to create more public space, connections and interaction. But sometimes you have to recognise that you can’t jump in with major interventions. In the fragmented context of much of Belfast’s inner city, you need small and sometimes piecemeal solutions that can be achieved with minimum resources. Grand gestures are very difficult to manoeuvre in this environment.

We are working on one redevelopment project that sits at the interface between a unionist and a nationalist community. During the Troubles, the area was a point of conflict, which meant housing along the boundary became vacated, derelict and eventually razed. A business centre was put there as a way of turning the blighted land into a place of ‘neutralised’ commerce. At the time, security concerns meant it became something of a fortress, with the buildings facing inwards on to a central car park. It has now been 20 years since the ceasefire, so we saw an opportunity to move things on. It meant making nuanced decisions, such as how best to open particular shop fronts on to the street without alienating either community.

We have to walk towards that kind of complexity, not away from it. It is down to us to instigate the kind of work we want to do and actively seek out challenging sites. We will approach the relevant people and propose ways of making a streetscape work better. There aren’t the opportunities to do high-quality architectural urbanism otherwise. The powers that be don’t identify these projects because there is too much concern about boundaries and segregation and not enough aspiration.

If we want change, we have to make it happen ourselves.

Balancing pragmatism and ambition

It would be a mistake to say that all of Belfast’s ills come from the conflict. A lot of problems are the legacy of poor planning and road infrastructure. Many parts of the inner city feel like they’ve been designed solely by road engineers as opposed to being the result of a multi-disciplinary approach with architects involved.

To create something of quality you need to interrogate restrictive regulations and that takes time, which cuts into your profits. There’s real glue in the system and even a minor planning application can get stuck. It has the knock-on effect of making it hard to do effective financial forecasting. But we have to play the game, so that means sitting down with road engineers and planners to fight for our projects.

We work with the realities of our context in a very pragmatic but also deeply ambitious way.

You also learn to savour the little-but-big victories,

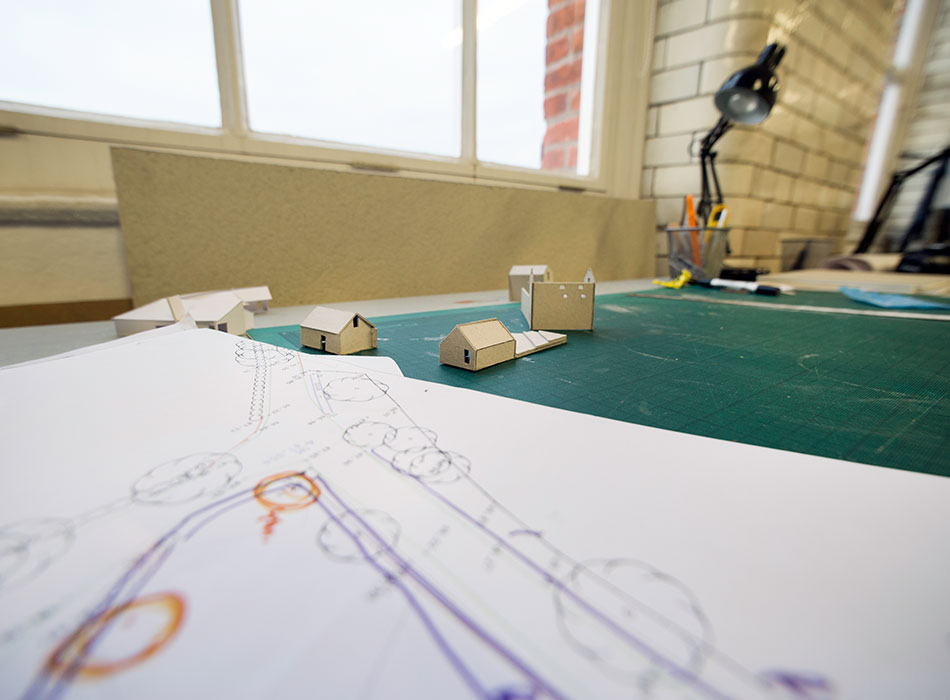

such as supporting the people who set up a small farm in one of the most socially deprived areas in the city. They identified a barren piece of land and decided to put a few sheep and goats on it. They didn’t know who owned it and didn’t really care. It was a completely subversive guerrilla tactic that enabled a small community to pull something back for themselves. We conducted some pro bono feasibility studies and then helped them to submit a planning application for workshops, animal sheds and garden spaces. For us that just epitomises what’s possible if you take a different attitude. We might be battling on all fronts but those are the type of experiences that show it’s worthwhile.

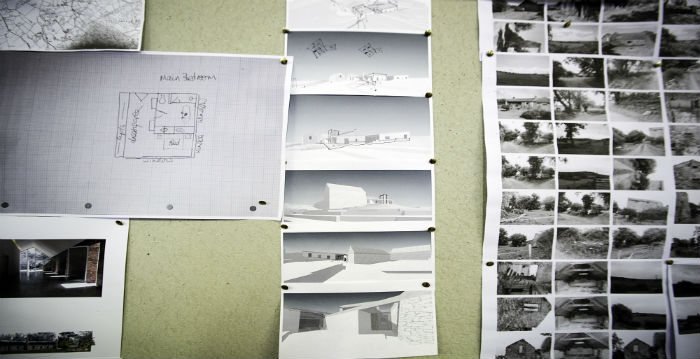

As a young practice, we recognise that we need to balance our aspirations to work on social housing and community projects along with a pragmatic need to generate income. At the moment, the majority of our work comes from one-off houses and work with private developers. We have to be a commercially viable practice and that means holding the different types of work we do in balance.

At the same time, we are still in touch with the original dream that brought us back here. We returned to Belfast with an optimism and a hunger to help repair the city, much like Berlin after the wall. In the end, it all comes down to what constitutes happy working. And we’re only happy if we’re doing interesting things, trying to win those small but important victories and making some positive difference to our home city.

Being a Practice Role Model means bringing an innovative approach to problem-solving

There is real scope to make it easier for young practices to thrive. For example, more open architectural competitions would enable smaller design studios to get a foothold and gain some visibility. We need to challenge ourselves to come up with creative ways of making the market more accessible to a range of practices.

Our own approach has been to sidestep some of the more frustrating aspects of the procurement process by getting out into the community and originating work that wouldn’t have existed without our intervention. Being a Practice Role Model involves taking an innovative approach to problem-solving, not waiting for someone else to fix it.

MMAS is one of nine Practice Role Models which represent our vision of what it means to be a successful RIBA Chartered Practice. Find out more about the Practice Role Model project and the other eight practices.