RIBA Collections research guide: LGBTQ+ spaces

The role of sexuality and gender identity in shaping spaces is a growing area of historical and architectural research. Throughout history, architectural spaces have formed sites where LGBTQ+ communities have explored, celebrated or concealed sexual and gender identities.

This guide signposts just a few of the resources and material relating to this topic available through the RIBA's Library and Collections. It is likely that many more stories are yet to be discovered, remaining untold because of legislation that forced LGBTQ+ individuals to conceal their identities or risk prosecution. In the UK, for example, sex between (specifically male) same-sex partners was a criminal offence until the Sexual Offenses Act of 1967. This guide aims to foreground some of these, often underrepresented, histories.

Find out more about the RIBA Collections and how you can access them, in-person and online.

Florence Cathedral

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the duomo (dome) of Florence Cathedral, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, was a site of clandestine homosexual activity – to the extent that the cathedral works board felt compelled to ban public access to it in 1552. Read more in our recent guest blog from Tom Butler.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a large number of photographs of the cathedral and duomo

- 19th century measured and topographical drawings of the cathedral by Frank Thomas Baggallay, George John Vulliamy and Robert Weir Schultz

- early and rare books discussing the architecture of Filippo Brunelleschi, such as the 1733 Descrizione e studi dell' insigne fabbrica di S. Maria del Fiore Metropolitana Fiorentina, featuring section drawings of the dome

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Ross King, Brunelleschi's Dome: The Story of the Great Cathedral in Florence (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000)

- Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence (Oxford University Press, 1996)*

Strawberry Hill House and Horace Walpole

Some historians have suggested that the writer and politician Horace Walpole (1717-1796) may have been gay or asexual. As the 4th Earl of Orford, he was a significant patron of art and architecture, and between 1747 and 1776 he worked alongside John Chute, Richard Bentley and James Essex to create Strawberry Hill House, a Gothic Revival style villa in Twickenham, southwest London. The villa’s unorthodox and exuberant aesthetic has been cited as a possible expression of Walpole’s queer identity. Read more in our recent guest blog from Holly James Johnston.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a number of photographs of Strawberry Hill, 1920s onwards

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- George E. Haggerty, ‘Queering Horace Walpole’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 46, no. 3 (2006)*

- Michael Hall, ‘Walpole’s Queer Gothic’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 163, no. 1416 (2021)

- Marion Harney, Place-Making for the Imagination: Horace Walpole and Strawberry Hill (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013)

- Paget Toynbee (ed.), Strawberry Hill Accounts: A Record of Expenditure in Building, Furnishing, &c., Kept by Mr Horace Walpole, from 1747 to 1795 (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1927)

- Matthew M Reeve, Gothic Architecture and Sexuality in the Circle of Horace Walpole (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020)*

- Horace Walpole, A Description of the Villa of Mr Horace Walpole... at Strawberry-Hill near Twickenham, Middlesex: with an inventory of the furniture, pictures, curiosities, &c. (Strawberry-Hill: Printed by Thomas Kirgate, 1784)

Kingston Lacy and William John Bankes

Kingston Lacy was the Dorset home of William John Bankes (1786–1855), who commissioned architect Charles Barry to remodel it in the 1830s. When Bankes was exiled in 1841 because of his homosexual encounters, he signed Kingston Lacy over to his brother. He continued collecting from abroad, sending art back to Kingston Lacy.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a number of design drawings by Charles Barry for the remodelling works at Kingston Lacy

- a number of photographs of Kingston Lacy, including those exhibited in the 1960 RIBA exhibition, ‘The Work of Sir Charles Barry’

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- David Adshead, ‘An Obelisk in Exile at Kingston Lacy’, National Trust Historic Houses and Collections (2012)

- Alastair Laing, ‘Special issue: The National Trust Historic houses and Collections’, Apollo, vol. 139, no. 387 (1994)

- National Trust, Kingston Lacy, Dorset (London: The Trust, 1994)

- National Trust, ‘William John Bankes and His Life in Exile’*

- National Trust, ‘Prejudice and Pride at Kingston Lacy’*

Cheyne Walk and Charles Robert Ashbee

Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) was an architect and key figure in the Arts & Crafts movement, who established the Guild and School of Handicraft. Although he was married to Janet Forbes, he described his love for other men as his “guiding light”, and was a member of the Order of Chaeronea, an ‘underground’ supportive network for members of the gay community. Interior spaces in the Arts & Crafts movement, such as Ashbee’s family home in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, have been discussed as sites of sexual freedom, where ‘respectable’ domestic life intersected with homosexual fellowship.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- interior and exterior photographs of Ashbee’s home at 37 Cheyne Walk, since demolished

- a significant number of drawings, including for houses, studios and student hostel at Cheyne Walk

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Felicity Ashbee and Alan Crawford, Janet Ashbee: Love, Marriage, and the Arts and Crafts Movement (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2002)

- Timothy Brittain-Catlin, ‘Chapter 3: Bullies and Sissies’, Bleak Houses: Disappointment and Failure in Architecture (London: MIT Press, 2014)

- Alan Crawford, C. R. Ashbee: Architect, Designer & Romantic Socialist (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985)

- Michael Hatt, ‘Edward Carpenter and the Domestic Interior’, Oxford Art Journal, vol. 36, no. 3 (2013)*

- Lionel Lambourne, Utopian Craftsmen: The Arts and Crafts Movement from the Cotswolds to Chicago (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, 1980)

- Fiona MacCarthy, The Simple Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981)

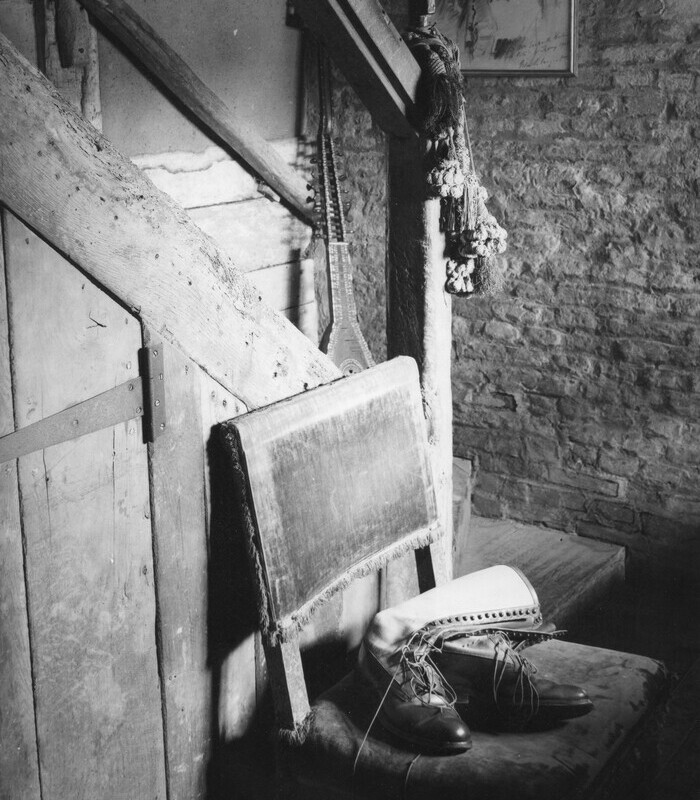

41 Cloth Fair and Mottistine Manor, Seely & Paget

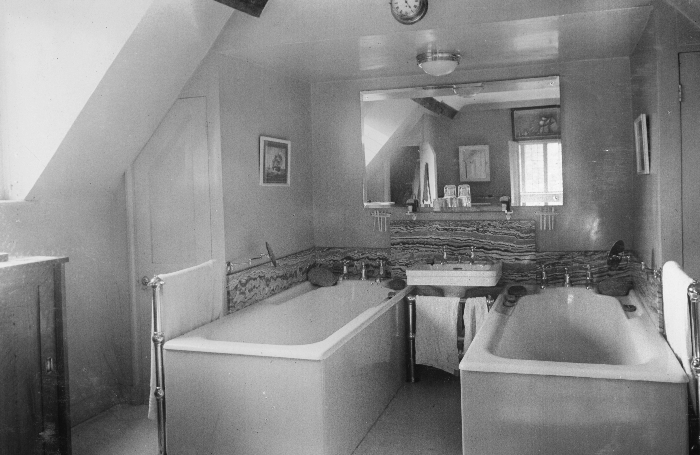

John Seely (1868-1947) and Paul Paget (1901-1985) were a twentieth-century architectural partnership probably best known for transforming Eltham Palace for the Courtauld family in the 1930s. Seely and Paget are widely understood to have had a romantic, as well as professional relationship. They lived and worked together at 41 Cloth Fair, a seventeenth-century merchant’s house in London that they restored and modernised. One of the design features they introduced was a bathroom adapted to include twin baths so that they could bathe at the same time. On the grounds of Mottistone Manor, the country seat of Seely’s father on the Isle of Wight, they designed a small “shack”, decked out with all the modern conveniences of the 1930s, where they would stay and work during visits to the estate. Read more in our article by RIBA Photographs Curator Justine Sambrooke.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- several photograph albums of Seely and Paget’s work, including photographs of the shack at Mottistone Manor, and the interiors of 41 Cloth Fair including the dual baths

- two albums of press cuttings, including articles showcasing Seely and Paget’s restoration of 41 Cloth Fair

- a significant number of drawings, including for Cloth Fair

- a photograph of Cloth Fair decorated as a 1952 Christmas Card, showing Seely and Paget in front of the building

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library):

- Clive Aslet, ‘An Interview with the Late Paul Paget 1901-1985’, Thirties Society Journal no. 6 (1987)

- Timothy Brittain-Catlin, ‘The Talented Mr Paget’, AA Files no. 67 (2013)

- Timothy Brittain-Catlin, ‘Chapter 3: Bullies and Sissies’, Bleak Houses: Disappointment and Failure in Architecture (London: MIT Press, 2014)

- Ella Carter (ed.), Seaside Houses and Bungalows (London: Country Life, 1937)

- Judith Habgood-Everett, Eltham Palace and Courtauld House: An Alternative Guide (Petts Wood: Latton Publications, 2000)

- Alan Powers, ‘Mottistone Manor, Isle of Wight’, Country Life vol. 188, no. 47 (November 1994)

- Adrian Tinniswood, The Art Deco House: avant-garde houses of the 1920s-1930s (London: Mitchell Beazley, 2002)

- Michael Turner, Eltham Palace (London: English Heritage, 2015)

- Small houses & Bungalows: Plans and Photographs of Architect-Designed Dwellings, 4th edition (The Builder, 1952)

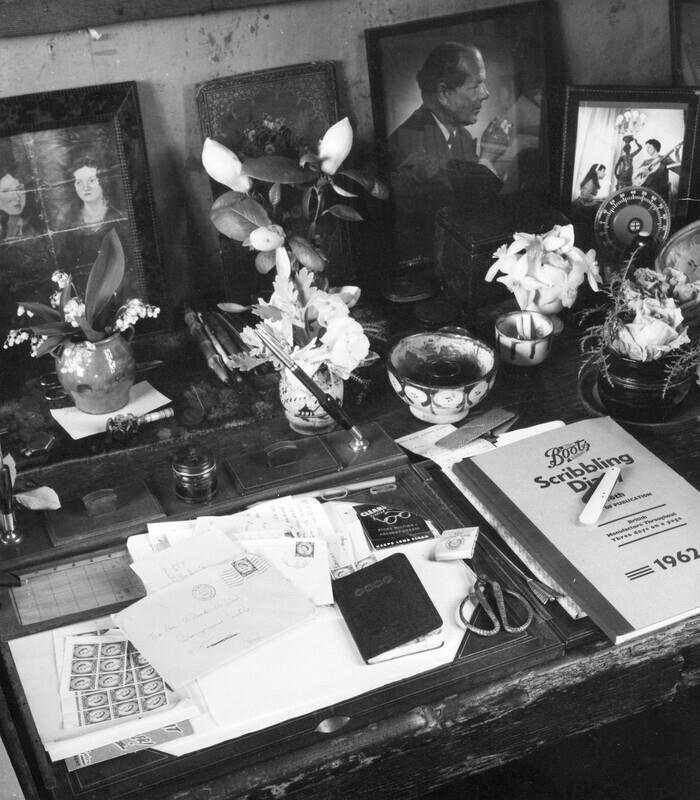

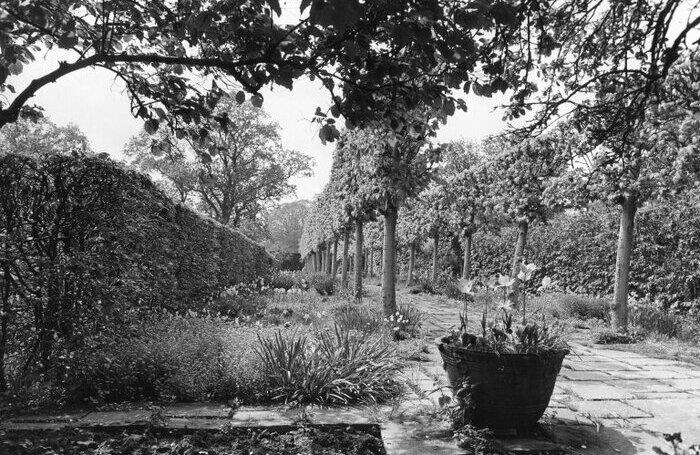

Sissinghurst Castle, Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicholson

The writer and garden designer Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) had an open marriage with her husband, diplomat Harold Nicholson (1886-1968), and both counted same-sex partners among their lovers. Sissinghurst Castle in Kent was the backdrop to some of these romances, and its garden design was the creative product of many years of collaboration between the married couple.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a number of photographs by Edwin Smith of Sissinghurst's interiors and garden during Sackville-West and Nicholson's time

- personal correspondence between Sackville-West and architectural historian John Summerson

- a biographical file for architect David Michael Hodges, who Sackville-West commissioned to design two farm labourers' cottages at Sissinghurst

- sketched designs by Edwin Lutyens for the dolls' house he designed for Queen Mary. Sackville-West wrote a miniature book titled A Note of Explanation for the dolls' house, the text of which is thought to have inspired Orlando by Virginia Woolf, with whom Sackville-West had a relationship

- material relating to Knole, Kent; the Sackville-Wests' ancestral seat and Vita's childhood home

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Sonia Baker, 'The Making of Sissinghurst', Traditional Homes vol. 6, no. 9 (1990)

- Jane Brown, Vita's Other World: A Gardening Biography of V. Sackville-West (Harmondsworth: Viking, 1985)

- Annunciata Elwes, 'Tale as Old as Time', Country Life vol. 211, no. 44 (2017)

- Emma Hughes, 'Away with Words', Country Life vol. 208, no. 4 (2014)

- James Lees-Milne, Fourteen Friends (London: Murray, 1996)

- National Trust, 'Vita in Love at Sissinghurst Castle Garden'*

- National Trust, 'Prejudice and Pride at Sissinghurst Castle Garden'*

- Troy Scott Smith, 'Peto and Vita', Country Life vol. 217, no. 39 (2021)

- Troy Scott Smith, 'Flooding the Garden with Romance', Country Life vol. 209, no. 42 (2015)

- Kristina Taylor, Women Garden Designers: 1900 to the Present (Woodbridge: Garden Art Press, 2015)

- Jack Watkins, 'Britain's Greatest Masterpieces: Sissinghurst Castle Garden by Vita Sackville-West', Country Life vol. 217, no. 41 (2021)

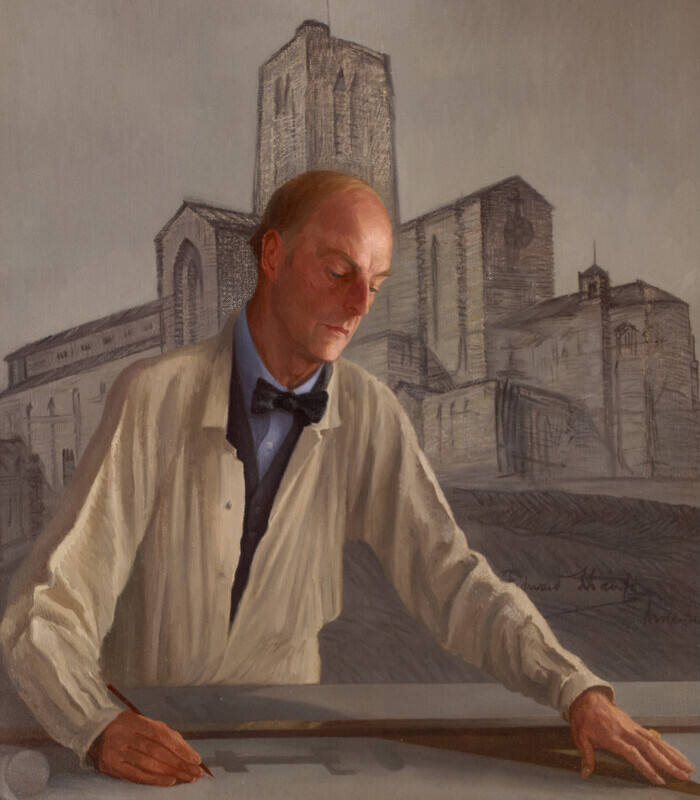

Bolton House and Gluck

Gluck (1895-1978) was a gender fluid artist, born Hannah Gluckstein, who commissioned architect Edward Maufe to design an artist’s studio at Bolton House in Hampstead, London. The studio was a key site for the formation of Gluck’s queer identity, where ‘Medallion’, a famous self-portrait with lover Nesta Obermer, was painted.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a portrait painting of Edward Maufe by Gluck. Maufe commissioned the portrait (inscribed “with love from Gluck”) in 1940, and is shown working on a plan of Guildford Cathedral in front of him, while the background is made of the signed original sketch that won him the cathedral competition in 1932

- contract drawings of Bolton House and Gluck’s studio

- interior and exterior photographs of Bolton House and Gluck’s studio

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Clare Barlow (ed.), Queer British Art 1867-1967 (London: Tate Publishing, 2017)*

- Amy De La Haye and Martin Pel (ed.), Gluck: Art and Identity (London: Yale University Press, 2017)*

- Guildford House Gallery, The works of Sir Edward Maufe: Exhibition of the Works of Sir Edward Maufe, R.A (Guildford: Guildford House Gallery, 1973)

- Diana Souhami, Gluck: Her Biography (Querkus Publishing, 1988)*

St Ann’s Court, Christopher Tunnard and Gerald Schlesinger

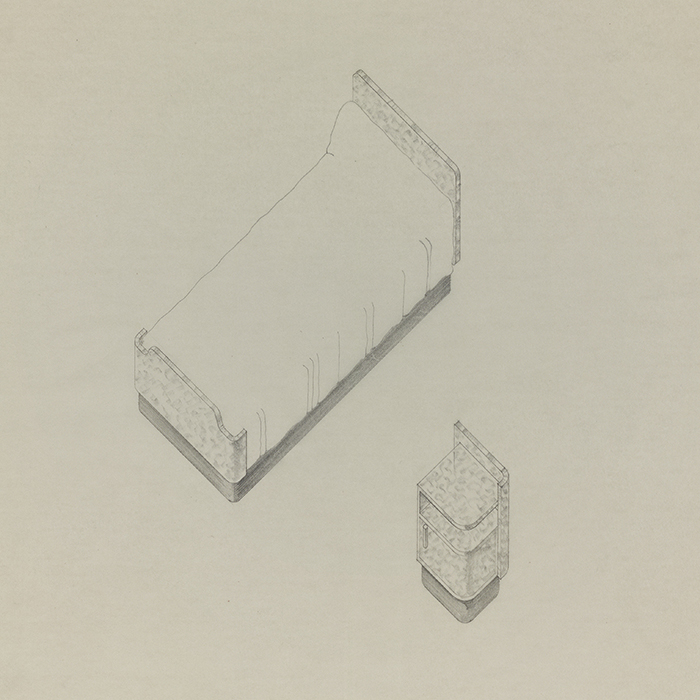

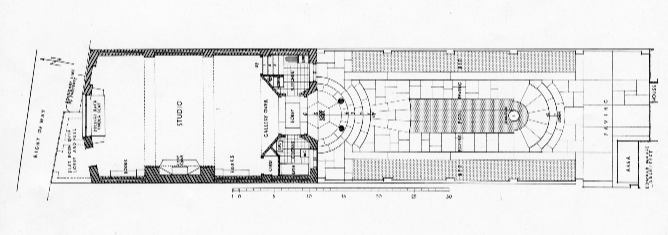

Stockbroker Gerald Schlesinger and landscape architect Christopher Tunnard (1910-1979) lived together at St Ann’s Court, a modernist house they commissioned from architect Raymond McGrath in the early 1930s. The design of the house's plan made it possible to divide the master bedroom in two when its residents had visitors, safeguarding Schlesinger and Tunnard's relationship at a time when men were prosecuted and imprisoned for homosexual activity. Read more in our recent blog article.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a number of exterior and interior photographs of St Ann’s Court

- several drawings for St Ann’s Court, including furniture designs such as a bed and bedside cabinet, perspective view of the study, and an axonometric view of the living room

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*)

- Nick Dawe, The Modern House Today (London: Black Dog, 2001)

- Donal O’Donovan, God’s Architect: A Life of Raymond McGrath (Bray: Kilbride Books, 1995)

- Historic England, List Entry 1260122: St Ann’s Court*

- Alan Powers, ‘High Ambition', Architects' Journal, vol. 215, no. 18 (2002)

- Christopher Tunnard, Gardens in the Modern Landscape (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014)

- Christopher Tunnard, A World with a View: An Inquiry into the Nature of Scenic Views (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978)

- Christopher Tunnard, The City of Man (New York: Scribner, 1953)

Glass House and Cathedral of Hope, Philip Johnson

Philip Johnson (1906-2005) came out publicly as gay in 1993 and was considered the best-known openly gay architect in the US at the time. The Glass House was Johnson’s own residence in New Canaan, Connecticut, built to his designs between 1948 and 1949 and since regarded by some historians as a “safe place where gay people could hide in plain sight” (Stern, 2012). In 1995 Johnson was commissioned to design a new church for the Cathedral of Hope, Dallas, whose mission was to spread a message of hope to the LGBTQ+ community.

Within the RIBA Collections are:

- a sheet of unidentified sketch doodles by Johnson

- a significant number of photographs of Johnson’s projects, including the Glass House

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*)

- Abby Bussell, ‘Philip Johnson unveils design for gay and lesbian church’, Architectural Record, vol. 184, no. 9 (1996)

- David Dillon, ‘Johnson’s Hopeful Design’, Architectural Record, vol. 186, no. 9 (1998)

- Alan Goldberg, John Morris Dixon and Michael Webb, ‘Special Issue: Mid-Century Modern Houses in New Canaan’, A&U, no. 584 (2019)

- Eric Nagler, ‘Mr. And Mrs. Johnson’, Metropolis (November 2006)*

- Adelle Tutter, Dream House: An Intimate Portrait of the Philip Johnson Glass House (University of Virginia Press, 2016)

- Anthony Vidler, ‘Glass House on the Couch’, Architectural Record, vol. 206, no. 3 (2018)

- Mark J. Stern, ‘The Glass House as Gay Space: Exploring the Intersection of Homosexuality and Architecture’, Inquiries Journal, vol. 4 no. 06 (2012)*

More Resources (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

One easy way to find relevant books in our library is to look for the classmark 721.011.2-055, which covers architecture, sex and gender. You'll find this at the far end of the library, on the left-hand side. If you need help, you can always ask our library staff.

- Julie Abraham, Metropolitan Lovers: The Homosexuality of Cities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009)

- Marlon Bailey, 'Structures of Kinship in Ballroom Culture', Architectural Review, vol. 248, no. 1479 (2021)

- Aaron Betsky, Queer Space: Architecture and Same Sex Desire (New York: Morrow, 1997)

- Aaron Betsky, Building Sex: Men, Women, Architecture and the Construction of Sexuality (New York: Morrow, 1995)

- Michael Charlesworth, 'Derek Jarman's Garden at Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, and his Avebury Paintings', Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes vol. 35, no. 2 (2015)

- Beatriz Colomina (ed.), Sexuality & Space (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992)

- Joe Crowdy, 'Queer Growth', Architectural Review, vol. 248, no. 1478 (2021)

- Historic England, ‘Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage’*

- Huw Lemmey, 'Out of Space', Architectural Review vol. 245, no. 1459 (March 2019)

- Forthcoming: Adam Nathaniel Furman and Joshua Mardell (ed.), Queer Spaces (London: RIBA Publishing, 2022)

- Elizabeth Otto, Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics (London: MIT Press, 2019)

- RIBA Radio, Episode 14: LGBTQ+ Lives*

- Jacob Ward, 'Won't you be my Neighbor?' Architecture (New York), vol. 91, no. 4 (2002)

- 'Toilette Pubbliche, Tokyo', Domus, no. 1054 (2021)

- RIBA Library: a Queer Literature Review by RIBA Discovery & Access team member, Lilliana Perrone