Revisiting the Collections

Revisiting the Collections is a new blog series where we invite people working to reveal and amplify underrepresented voices in the cultural and built environment sectors to share their reflections on material in the RIBA Collections. Through this series, we hope to enhance collective understanding of our collections, forge fresh collaborations, and tell new stories about the history of architecture.

In this first blog, Tom Butler explains how the dome of Florence Cathedral reveals the presence of queer stories at the symbolic heart of the Western architectural tradition. Tom Butler is a researcher and creative producer exploring narrative, place and the future of the built environment. He teaches on MA Narrative Environments at CSM and is a Doctoral Researcher with Brunel University and the Museum of London.

Revisiting Florence's Duomo

The duomo (dome) of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore is among the most celebrated structures of the Renaissance, a vast terracotta-tiled mass that still dominates Florence, nearly six centuries after its construction. Lesser known is how the duomo reveals the presence of queer stories at the symbolic heart of the Western architectural tradition.

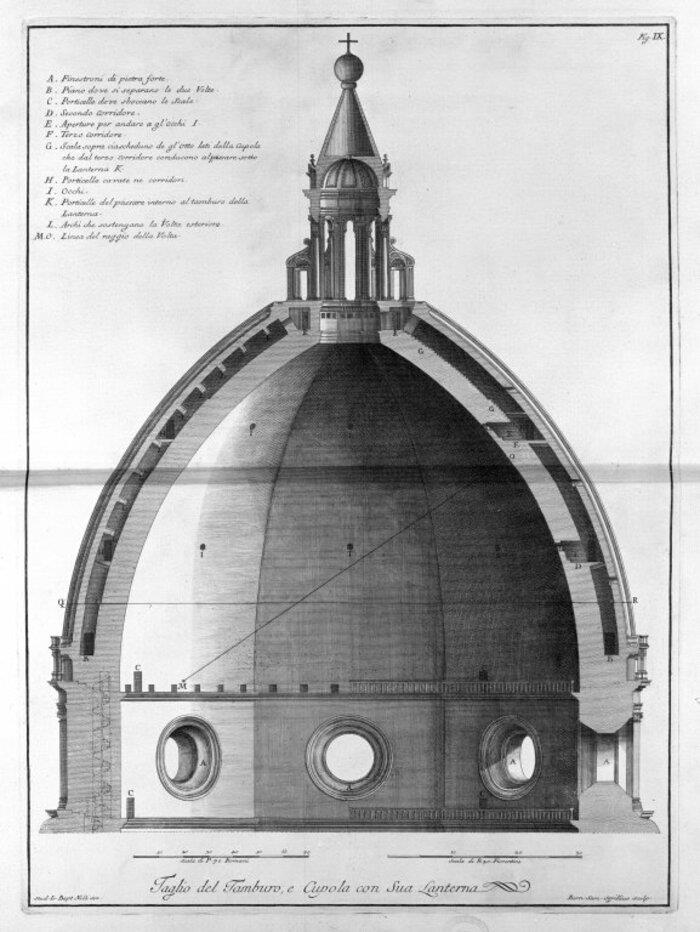

The completion of the dome in 1436 was so improbable that the people of Florence called it a “magic trick,” the miraculous solution to a 100 year conundrum: how to build a dome spanning 46 metres, rising from an octagonal base several storeys high, and to do so without flying buttresses or conventional scaffolding? Filippo Brunelleschi, the father of Renaissance architecture, was the magician responsible. Brunelleschi’s "trick" comprised two domes, one on top of the other: the bricks of the inner dome are arranged in a self-reinforcing herringbone pattern encircled by four horizontal stone and chain hoops; this is connected to the outer dome by 24 vertical arched ribs, eight of which are visible on the dome’s exterior.

Brunelleschi’s scheme was a revelation and remains the largest spanning brick dome in history. Yet beyond this technical achievement, the stories that encircle the dome also tell us much about LGBTQ+ lives, past and present.

Sex and sexuality in fifteenth century Florence were conceived very differently to contemporary Western ideas. Sex between men was commonplace and such relationships and encounters were usually intergenerational, expressing established power relations and socially defined sexual roles. Nevertheless, while same sex erotic relationships were an established part of masculine identities, they transgressed moral and religious codes of the time. In 1432, as Brunelleschi’s duomo neared completion, the authorities established the Ufficiali di notte (the Office of the Night) to prosecute male homosexual activity. Tamburi (boxes) were also placed throughout the city in strategic public locations, allowing citizens to make anonymous accusations of moral crimes. Punishments ranged from fines, lashing and imprisonment, to exile or death by burning. Rather than conventional histories or records, it is the legal archive of criminalised activity that reveals the pervasiveness of same sex love and desire during this period.

This social and cultural context may explain why details on the life of Brunelleschi are limited beyond his artistic and architectural output. He was born in 1377 into the affluent family of a public notary and trained as a goldsmith, watchmaker, and sculptor. In 1401, he lost a public competition to design the bronze doors of the Florence Baptistry to his great rival Lorenzo Ghiberti. This loss is believed to have inspired a decision to leave Florence for Rome. Here he studied the city’s classical ruins alongside fellow sculptor Donatello, with whom some historians have suggested he had a romantic relationship. However, as with many homosexual relationships in history, this assertion seems to require a higher burden of proof than for heterosexual relationships.

Brunelleschi returned to Florence around 1416 where several architectural commissions followed, informed by his knowledge of ancient Roman building techniques. These culminated in the commission for the duomo, and construction commenced in 1420. Brunelleschi was also responsible for several artistic and technological innovations, including being the first to devise a system for the laws and principles of perspective, a discovery that would revolutionise Western art and architecture. Brunelleschi died in 1446, just as work began on the dome’s lantern. In recognition of his achievements, Brunelleschi was honoured with a burial in the crypt of the cathedral he had helped to complete.

Brunelleschi’s duomo became an important symbol of Florentine power and pride. It also provided a secluded space for male homosexual encounters: in 1482 a man was convicted for having sex in the cathedral’s cupola. Its attraction as a place for men to meet continued, to the extent that public access was banned in 1552. In his book on homosexuality and male culture in Renaissance Florence, Michael Rocke cites a report by Giovanni Conti, a counsellor of Duke Cosmo I, that recommends the closure of the cupola “in order to obviate the obscenities and wrongs that are committed daily in that sacred space.” Conti reports seeing young males practising “many indecencies, kissing each other and giving each other the tongue.” For many, the dome of a cathedral may not be the most obvious place for a sexual encounter, and yet its use for this purpose highlights the moral and spatial constraints that existed in Renaissance Florence, in which male homosexual love and desire was forced from the public gaze.

Five centuries later, social and legal constraints on LGBTQ+ lives have greatly reduced, and attitudes have improved in much of Western Europe. Queer lives as we understand them today are far more visible. Spatially, however, different constraints remain, affecting a wide range of queer spaces. Research by UCL Urban Lab and Raze Collective, for example, reveals that London alone lost 58% of its LGBTQ+ venues between 2007 and 2017, more than twice the rate of pub closures over a similar period. This decline is likely to be further exacerbated by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

Contemporary losses of queer spaces have been widely attributed to the rise of dating apps and the mainstreaming of LGBTQ+ identities. Yet dedicated and safe spaces remain vital for LGBTQ+ communities as places of social encounter, self-expression, and support. This is especially true for groups excluded from mainstream (i.e. white and male) gay culture. Some high profile closures have been prevented by legislation including Asset of Community Value status and initiatives such as the LGBT+ Venues Charter in London. However, protecting queer spaces across the country from rent increases, licensing issues, and gentrification pressures requires more than a “magic trick,” and more must be done.

Archives like the RIBA Collections have a part to play in resisting such erasures. While legal records of early Renaissance Florence can inform our understanding of LGBTQ+ lives at the time, recording the unique architectural expression of queer spaces, such as the often creative and informal reuse of delipidated or abandoned spaces and buildings, alongside more formal architectural records can counter the exclusion of LGBTQ+ narratives. As more queer spaces disappear, the need to document them becomes ever more vital to ensure that these stories and spatial expressions do not continue to be lost. Archives can provide the power of historical perspective and reveal the presence of queer stories, even in unexpected places such as the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore. Crucially, archives can continue to capture the presence and unique materiality of LGBTQ+ spaces both past and present.

Find a model of the duomo's lantern on display in the V&A + RIBA Architecture Gallery, read more stories inspired by the RIBA Collections, or browse RIBApix for 100,000+ digital images of our historic collections.