Revisiting the Collections is a new blog series inviting people working to amplify under-represented voices in the cultural and built environment sectors to share their reflections on material in the RIBA Collections. Through this series, we hope to enhance collective understanding of our collections, forge fresh collaborations, and tell new stories about the history of architecture.

In this piece, Sarah Ackland calls for collections like RIBA’s to do more to proactively address the under-representation of women architects from architectural archives. Sarah is a core member of Part W, an intergenerational action group founded by Zoë Berman and formed by women from diverse backgrounds, who work together in a volunteer-led capacity to campaign for gender equity in the built environment. Sarah is also a PhD candidate at Newcastle University, architect at muf architecture/art, and design tutor.

‘You can’t be what you can’t see’ said Marian Wright Edelman, a children’s rights campaigner in the US, a phrase commonly shared by activist groups campaigning for greater visibility. Architecture groups such as Paradigm Network, Black Females in Architecture, Afterparti, Decolonise Architecture, Muslim Women in Architecture, Part W and Sound Advice are working to diversify and create more equality in this majority white and male profession. Yet while change starts from the ground up, we must also dig into our history to ensure that equality and decolonisation can flourish. That includes our archives and records, so I investigated whether I could find the ‘firsts’ in the RIBA archive: the forgotten women who first broke through the patriarchal gates of the profession, and led the way for others.

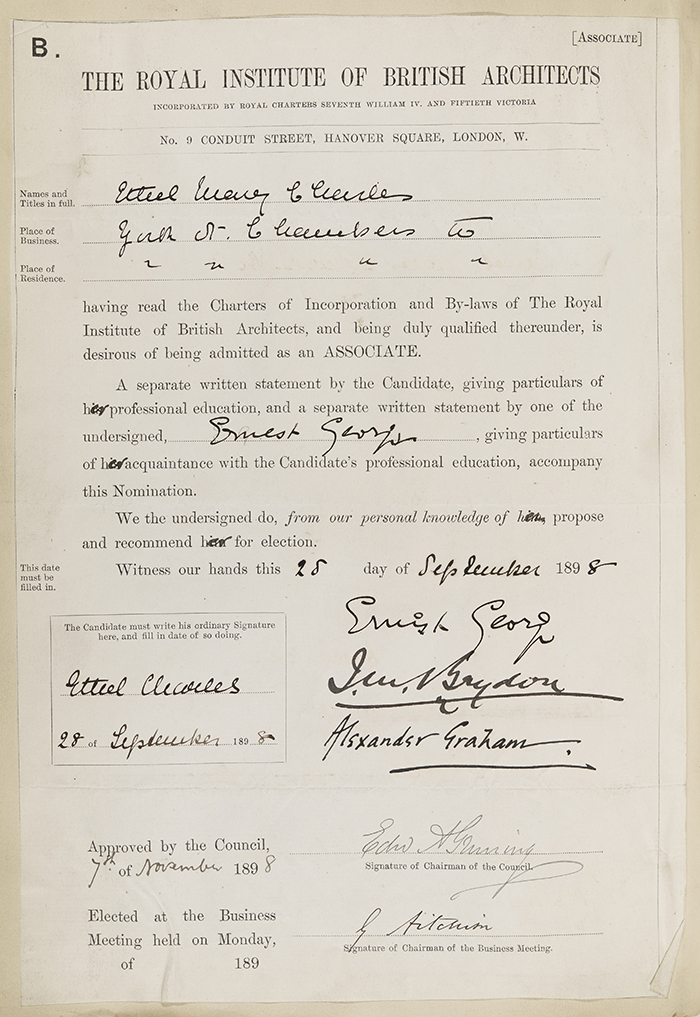

The lack of documentation I found reveals the limitations and biases which exist within archival materials, including past collecting and recording methods. The archive collection documents many architects who fit the traditional canon (white, male heterosexual and cis), and reveals processes that prevented the inclusion of others. The nomination forms to join the RIBA included only male pronouns until at least 1968, and it’s unclear when female pronouns were introduced. There remains urgent work still to be done to ensure the inclusion of all identities.

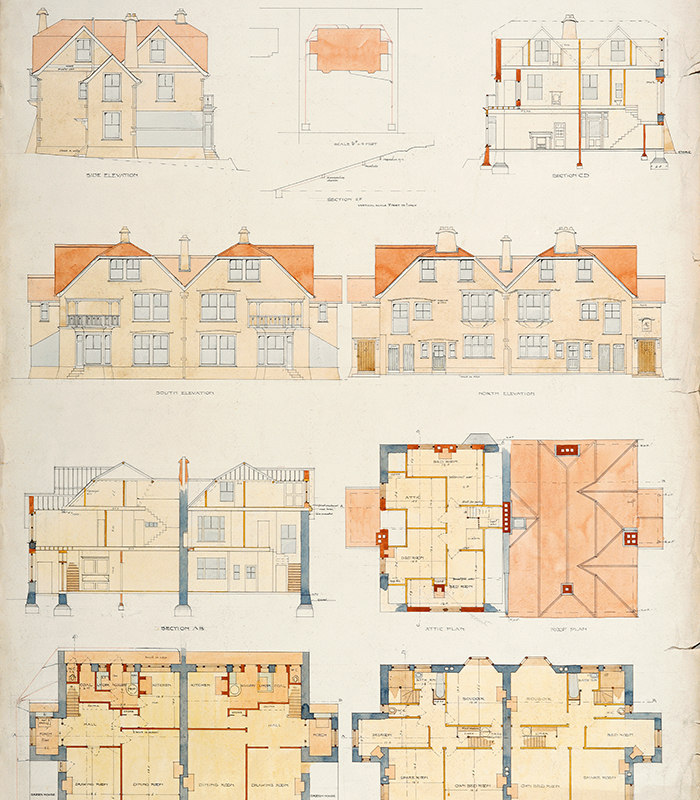

Ethel Charles was the first woman to gain membership to the RIBA in 1898. Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham (1632-1705) is sometimes credited as Britain’s first female architect but Charles, having fought for her place at the RIBA, is more often celebrated as the ‘first female architect’. She has even had her own ‘Ethel Day’, launched in 2017 by then RIBA President Jane Duncan. Charles is thoroughly documented in the archives through her detailed drawings and more evocative sketches, alongside her nomination papers.

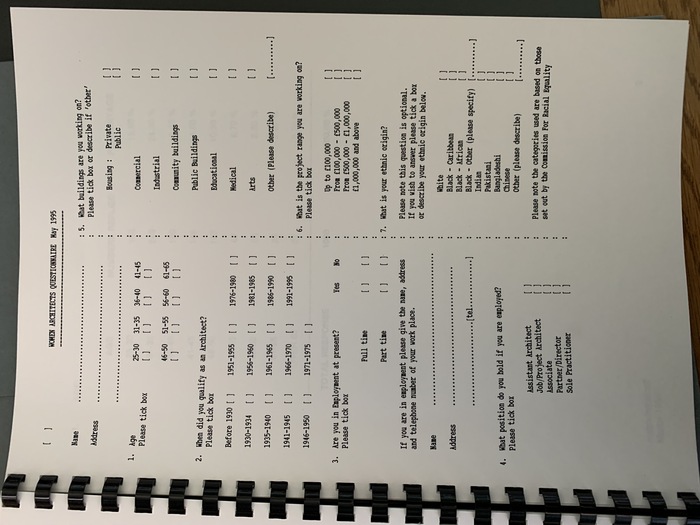

By contrast, the first black woman to become a member of the RIBA is unknown – revealing the gaps in recent attempts to better foreground architects who entered the profession despite the systemic inequalities they faced. Surveys undertaken in 1996 by Matrix, the feminist design collective, revealed that of the 966 women architects in the UK who responded, 15 were black. This equated to 1.47% of respondents, compared with 92% of respondents who were white. Recent ARB surveys indicate that, to this day, only 1% of registered architects are black. Ann De Graft-Johnson of Matrix Collective has written how, while studying, she only encountered one other black woman. De Graft-Johnson went on to design the Jagonari Women's Centre in 1987 with Matrix, a building well documented in Matrix’s archive, currently on view at The Barbican. The women’s centre, in Whitechapel, east London, is absent from the RIBA Collections.

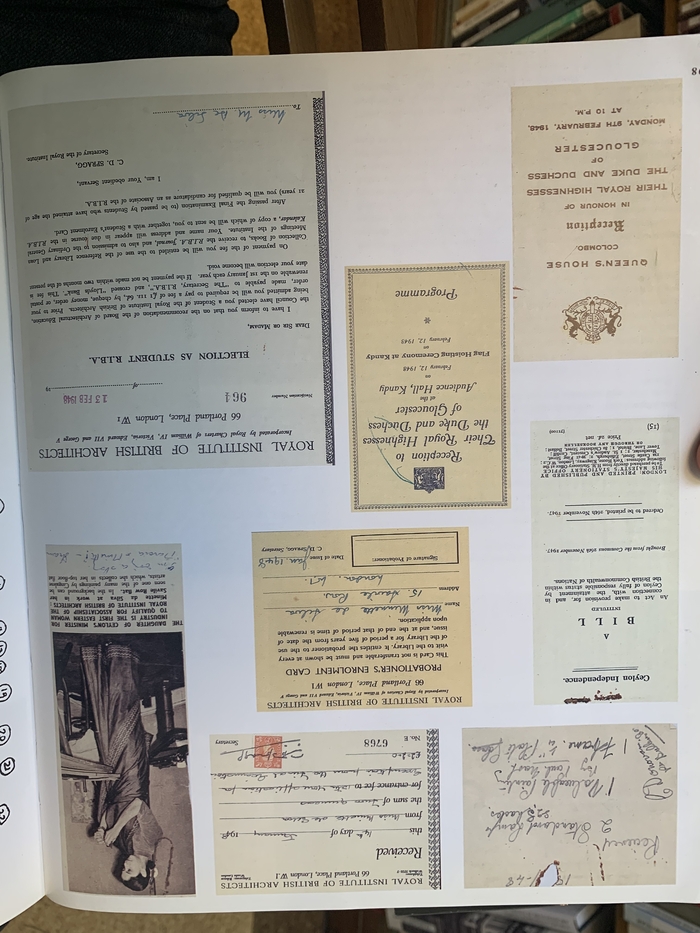

The widely acclaimed American architect Elizabeth Carter Brooks is also not represented in the RIBA Collections, despite her tireless campaigning for preservation of black heritage buildings in the US; campaign work which she is today celebrated for. The first Asian woman to become an Associate of the RIBA was Minette De Silva, who was awarded the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects Gold Medal following her death. A close friend of Le Corbusier and Pablo Picasso, she is best known for her work on Karunaratne House in Kandy, the artist’s home for Segar, and the Kandy Art Association and Centenary Culture Centre. Yet there are only two photos of De Silva in the RIBA Collections, and none of her work. In comparison, the RIBA holds vast documentation on Jane Drew, a contemporary to De Silva with links to Le Corbusier. It is clear that white women have been better documented than non-white. A catalogue search on Le Corbusier or Alvar Aalto shows how documenting male work has comparatively been prioritised over women’s.

Interestingly, De Silva proactively battled her own erasure from history by writing her autobiography, 'The Life & Work of an Asian Woman Architect', of which the RIBA Library holds a copy. De Silva herself explained her battle for recognition: “I was dismissed because I am a woman. I was never taken seriously for my work.” She crafted this book to reflect her work; from saris, to spaces she designed, to the design of her studio. She included images of herself and ensured her legacy remained. The book reflects the rich materiality of her work, much of it lost. Her own home in Sri Lanka was plundered after her death in 1998 and now stands in ruin.

Many media articles about De Silva commented on her physical appearance more than her work, including exoticizing language that recalls racist tropes. Meanwhile, the private lives and behaviours of male architects (Le Corbusier was known to be a Nazi sympathizer, while Adolf Loos was convicted for paedophilia), often generously escape any mention.

Should women in architecture today collect their own material to ensure parity of with their male counterparts in collections? This can’t be the answer. Existing collections, including those of the RIBA, need to proactively rectify their historic biases to create meaningful change and better support the representation of women. Men need to be part of this change too. The RIBA can play a critical role in making and supporting the change. It is crucial to not further burden women with this task, so that everyone is able to find architects of the past and present, who have walked this path before us.

We cannot be what we cannot see.

Follow the contributors on social media

Instagram: @saraheackland @PartWCollective

Twitter: @sarah_ackland @PartWCollective