The history of the RIBA President's Medals: Thomas Simons Attlee

In a series of blog articles surfacing surprising stories from the archives of the President's Medals, part of the RIBA Collections, historian Matthew Wells uncovers the work of the 'other' Attlee brother.

Over the past 187 years, several winners of the RIBA President’s Medals have focused on questions of changing society through architecture. For many young architects, the question of reform is not found in the design of individual buildings, or their construction, but in the make-up of society.

Thomas Simons Attlee (1880–1960), older brother of former Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, won the Essay Medal in 1914 for his work ‘The influence on architecture of the condition of the worker’, influenced by J. A. Hobson's book The Evolution of Modern Capitalism (1894). After studying history at Oxford, Attlee was apprenticed to Charles Edward Barry in 1902, and took his final exams for RIBA in October 1906. After joining the institute as an associate member, Attlee’s training continued with courses in sanitation, joinery, and other specialisations, which he combined with philanthropic work with his brother, Clement, in London’s East End.

Attlee’s two interests – social reform and architecture – were tightly intertwined. Alongside volunteering for Christian charities in east London, Attlee taught continuing education classes in Oxford and at the London County Council (LCC) School of Arts and Crafts, and qualified as an Associate of the Royal Sanitary Association.

In his essay, Attlee noted how the conditions of the prize (to take an architectural subject and make a useful contribution to knowledge through its research) led him to focus on the treatment of construction workers in British society. Drawing on writers such as John Ruskin, William Morris, and Auguste Choisy, Attlee’s underlying principle was that architecture was a ‘cooperative art’, and as a result, must be connected to collective goals rather than individual needs.

Attlee's essay covered buildings from Karnak in Egypt to King’s Cross in London, looking from the past to the future as he considered contemporary developments in trade unions and collective democratic organisations during the early 20th century. In particular, Attlee’s attention was drawn to one organisation connected to the Arts and Crafts movement. His essay describes Charles Robert Ashbee’s ‘ingenious scheme’ at the Guild and School of Handicraft, an experimental group of art workers that was based in the East End between 1888 and 1895. Focused on hand-made objects, the guild operated as a cooperative, enabling craftsmen to learn and work together on jewellery, metalwork, enamelling, furniture, and (later) bookmaking.

The significance of Attlee’s prize-winning essay is shown by an eight-page review published in the December 1914 edition of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. Written by the influential American architect Frederick L. Ackerman, the review summarised Attlee’s argument, praising the essay’s contextual reading of construction work in different societies and making a valuable contribution to our understanding of the role of an architect in contemporary life.

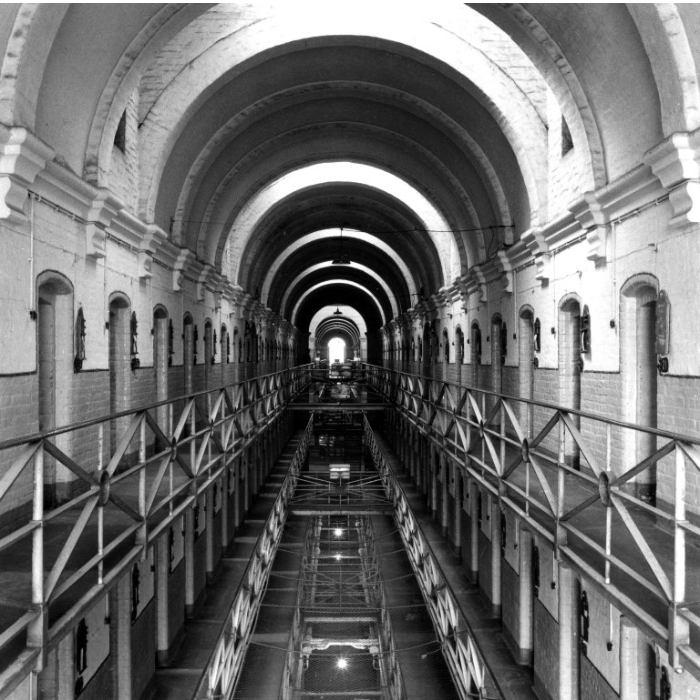

When Ackerman’s review was published during the first few months of the First World War, Attlee was working on various housing projects and lecturing for the LCC. He added a new talk to his series, ‘Historic Towns of the War Area', that examined cities in northwest Europe. As a Christian and a member of the strongly anti-war Independent Labour Party, Attlee refused conscription in 1916, becoming what we now call a conscientious objector. Attlee’s refusal to fight in the war led to his imprisonment in London, first in Wormwood Scrubs and later in Wandsworth Gaol, from January 1917 to April 1919.

Following the war, Attlee became an important part of a non-violence organisation, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which published a series of books. One title was an expansion of Attlee’s prize-winning essay. A final chapter was added on new collective institutions for construction workers, published as 'Man and His Buildings' (1920). He and his family moved to Cornwall shortly afterwards, where Attlee became involved in local politics through Christian groups, taught students at a Workers’ Education Association in Truro, and wrote for magazines and architectural journals.

This article is part of a project, generously funded by Footwork Trust, to catalogue, research, and interpret the RIBA President's Medals archive and make this valuable wealth of material available to everyone. To view material in the President's Medals archive, please contact drawingsandarchives@riba.org.

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Frederick L. Ackerman, ‘Review: The Influence of Architecture on the Condition of the Worker’, Journal of the American Institute of Architects vol. 2, (December 1914), 547–555

- Peggy Attlee, 'With a Quiet Conscience: Biography of Thomas Simons Attlee' (London: Dove & Chough, 1995)*

- T.S. Attlee, 'Man and His Buildings', Christian Revolution Series (London: Swarthmore, 1920)