"This Dilemma": Collecting and constraints at the RIBA

Chater Paul Jordan is a researcher in the visual arts, architecture, and history with a particular focus on postcolonial cultural experience and decolonial theory. He recently took part in a research project at Christ’s College, Cambridge, investigating the legacies of enslavement at the College.

Chater studied History of Art at the University of Cambridge, having previously taken a course in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins. Here, he explores the shaping of the RIBA Collections, to consider what absences and silences they might be defined by.

“Anyone thinking of using the archive would be mistaken in expecting to find in it material on issues or subjects which many at the time accused the Institute of neglecting, or in hoping to get a comprehensive view of matters in which it favoured a single interest.”

Pithily forewarned by Robert Thorne in his introduction to Angela Mace’s The Royal Institute of British Architects: A Guide to its Archive and History, I began an enquiry into how the RIBA Collections overlook certain alternative narratives and histories. The role that archives have in shaping histories has perhaps been underappreciated, but the spotlight has recently taken focus on national institutions and their archives as sites evidencing the exclusion and suppression of underrepresented groups (often problematically characterised as the “other”). It was in this context that I sought to investigate what histories might have been obscured through archival silences.

The RIBA’s institutional archive charts the body’s 188+ year institutional history. Thousands of papers, reports, minutes, and letters tell the story of the Royal Chartered body through two world wars, several relocations, and plenty of committee wrangling. Alongside these are the RIBA Collections more broadly: drawings, photographs, manuscripts, artefacts and books collected during the institute’s history as specimen examples of architecture. Focusing my attention on the former, I went in search of clues as to the formation of the latter, using the RIBA’s institutional history to shed light on the development of its collections during the second half of the 20th century, and the possible absences within.

Thorne’s warning hints at the potential pitfalls of such an endeavour. Wading through the tranche of material on offer in the institutional archive, the challenge of the task became clear. At this point, all I could offer in conclusion was agreement with Thorne’s warning and a hopeful call for collections, and RIBA, to do more for the neglected “other” (as concluded by Sarah Ackland and Tom Butler for their respective articles in this series). While this article does endorse these points, I also hoped to begin uncovering the very factors that can make archives and collections such an unyielding resource in the search for alternative histories.

Uncovering "The Dilemma"

The 1960s and '70s, chronicled in the Librarian’s Papers within the RIBA's institutional archive, proved an interesting period for the RIBA Drawings Collections, as the department prepared to relocate them from the RIBA headquarters at 66 Portland Place to new premises at 21 Portman Square, which opened in May 1972. The papers reveal it to have been an anxious time for the institute, as evidenced in various appeals to its members. For instance, a 1969 notice read, "We have already outgrown our premises and resources, and the situation is made yet more acute by the need for proper representation and display of modern drawings. There is no longer room to house this magnificent collection in the premises of a busy professional institute."

Consequently, the subject of the papers seems chiefly concerned with the very survival of the collections, rather than their expansion or diversification. By 1968, the Library Board had established that the funds needed to rehouse the collections were “in the region of £200,000”. Bolstered by Harold Samuel’s promise of £50,000, the group set about their “determined effort” to raise “four or five times this amount,” to resolve what Librarian David Dean termed “this dilemma”. Yet by September 1970, the project had only £56,193 cash to hand, with a promise of £7,142 by the following June. Sifting through the papers, one finds a subsequent series of appeals to prominent RIBA members, foundations and companies to raise the remaining sum. The frank manner in which each prospect was profiled provides more insight into an anxious time. Prospects are characterised variously as “very wealthy,” “notorious for not replying” and “difficult”. The Board further toiled over the simple question “How rich are the ‘rich’ architects?”. What may amuse modern readers as a timeless adage for the profession also reveals a tense time for the department, as funding and space were sought to accommodate both the existing collections and hopes for their future expansion. Funds were also raised through the sale of watercolour paintings by John Sell Cotman, for £39,000, to the newly established Mellon Centre for British Art and British Art Studies. Illuminating curatorial priorities at the time, the watercolours were sold on the basis that they were “not architectural designs of the type which the Drawings Collection aims to house, and were not, of course, the work of an architect". The sale of the Cotmans to the Mellon Centre is made more interesting considering Paul Mellon personally donated £5,000 toward the project.

Other notable donations included Henry Heinz’s gift of $28,000 USD (commemorated in the dedication of the Heinz Gallery at Portman Square) and a £5,000 joint-donation from the Chartered Consolidated Mining, Anglo-American plc., and De Beers Mines; the colonial enterprise founded by Cecil Rhodes. How best to communicate the latter donation was the subject of a great deal of correspondence, and a July 1969 memo ultimately deemed it “a matter for report, and not for discussion”. Could this reluctance to discuss the donation indicate the same sense of unease a contemporary reader might feel, understanding the source of funding? Incidentally, the donation came at a time of increasing international alarm at the system of apartheid in South Africa.

In pursuit of answers

In search of an explicit acquisition policy for the period, I turned to former RIBA Curator Margaret Richardson’s 1985 article In Pursuit of Drawings, which reflects on twenty years of the RIBA’s collecting. It opens with the revelation that, in 1964, the collection “only had one” drawing by a “celebrated living architect” (the RIBA Drawings Collections now counts thousands of works by current architects among its ranks). It might be illuminating here to adjust Richardson’s emphasis and consider what constitutes a “celebrated” architect. In Richardson’s case, Mies van der Rohe and Edwin Lutyens each claimed this honour. Richardson outlines a policy of acquisition, spearheaded from 1961 by RIBA Drawings Curator John Harris, to collect drawings that “would represent the best examples in the past”. Here, Richardson’s acknowledgement that “judgement and prejudice will inevitably be involved” in the selection of new material, is revealing. She recalls a “heated meeting” about whether the RIBA should acquire drawings in the Modern (or ‘International’ style). Despite certain “antiquarian leanings”, and to the dismay of some committee members, the “Modern cause prevailed,” reports Richardson. Drawings by Maxwell Fry, Powell & Moya, and Sir Hugh Casson consequently graced the collections. Once again, Thorne’s forewarning rings true.

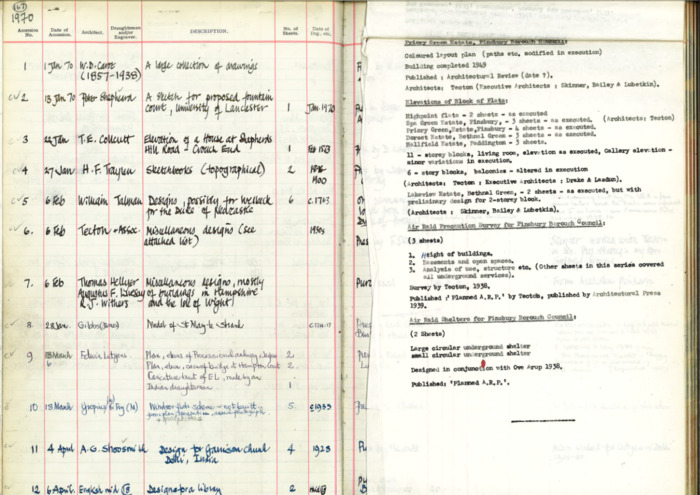

As we might have suspected, the sought-after “best examples” tended to represent a normative white patriarchy. There are some limited exceptions, evidenced in the accessions registers of the period. An entry on 6 March 1970 describes a caricature bust of Edwin Lutyens “made by an Indian draughtsman”. A search of the online RIBA Collections catalogue reveals 86 entries for works by similarly anonymous “unidentified 19th century Indian” draughtsmen. What initially seems discouraging might in fact invite an opportunity to diversify accounts of the collections, beyond simply searching for the ‘first’ unidentified 19th- century Indian draughtsman. While the Indian Institute of Architects was established in 1917 and the regulatory Council of Architecture only in 1972, a whole tradition of architects, masons, and draughtspeople clearly existed in India before colonial codification. Many were subsumed within the colonial enterprise, their legacy marked by this presence of absence: the unidentified 19th- century Indian draughtsman.

Reflections

As we begin to consider diversity and inclusion as central consideration of historical research, it seems crude to relentlessly single out individual (while worthy) ‘pioneers’. Instead, this article hopes to invite further research into the formation, evolution, and outreach of the collections, beginning to disclose those muted histories and in turn slowly disentangle “this dilemma”.

The department’s move from 66 Portland Place to 21 Portman Square offers one case study in understanding how the collections have been formed. The period appears defined by concern toward saving existing assets, arguably at the expense of the collections’ expansion or diversification. However, the Librarian’s Papers have (as described in catalogue records) “been heavily weeded by past librarians” and, like most archives, cannot hope to tell the story on their own. While responsible weeding is a standard archival practice, it is intriguing to consider what might have been lost. Chief Curator Charles Hind points out that a search through the individual archives of some of the architects may fill some of the gaps in the stories of the institutional archive, hinting at the ways in which archives (with the ways in which they structure information and material) can prove fickle resources.

The RIBA Collections, including its institutional archive, are most helpfully thought of as a conscious resource, rather than an objective vault of evidence, reflective of the RIBA itself. Highlighting how the collections are constantly evolving, Hind describes today’s approach to collecting as “the collective memory of the architectural profession in the United Kingdom and its members worldwide”.

In the search for alternative histories within the profession, the future lies in using the collections as a point of comparison with other repositories, to identify those elisions and areas of absence at a broader scale, reconciling that otherwise fractured collective memory. This process would undoubtedly begin to uncover such histories without resorting to the seemingly inevitable search for “the first…”.

Find out more about the RIBA Collections and how you can access them.