‘Planning for the Future’, the government’s white paper on planning reform published earlier this year, calls for radical reform of the planning system "unlike anything we have seen since the Second World War". The proposed reforms centre on a dedication to beauty and design-led community engagement which is commendable. But how should this be delivered and what resources already exist that the government can draw on?

In this blog post, part of a series published for the Future Place programme, Ben Derbyshire reflects on the white paper and the proposed reforms. Drawing on his experience as a practitioner – and as Immediate Past President of RIBA – he sets out a bold vision for how national agencies and professional bodies can work together with the government, local authorities and local communities to deliver healthy, sustainable and joyful places for the future.

A new national body

The Secretary of State, Robert Jenrick, has set out plans to establish a new national design body. With substantial resources at its disposal, the body will be putting ‘beauty’ at the heart of the planning system and it intends to support communities in producing binding design codes for their local area – thereby ensuring that design quality and existing local character are recognised and conserved.

Nicholas Boys Smith, Director of Create Streets, will chair a new steering group that will advise the government on how best to help communities set locally derived rules for development in their neighbourhoods. The group will also ensure that design and high environmental standards are fundamental to every planning application – "the first time in history" that beauty will be at the heart of the planning process, says the ministry.

But is that really true?

Back to the future

Back in 2016, as President-elect of the RIBA, I approached Lord Best – a life-long champion for quality in housing and placemaking – to help me identify the central issues inhibiting the delivery of high-quality neighbourhoods. Involving stakeholders from across the sector, we convened a series of seminars and whittled away at the issues. It quickly became clear that the main bottleneck was the lack of resources in local authorities as well as difficulties with delegating decisions.

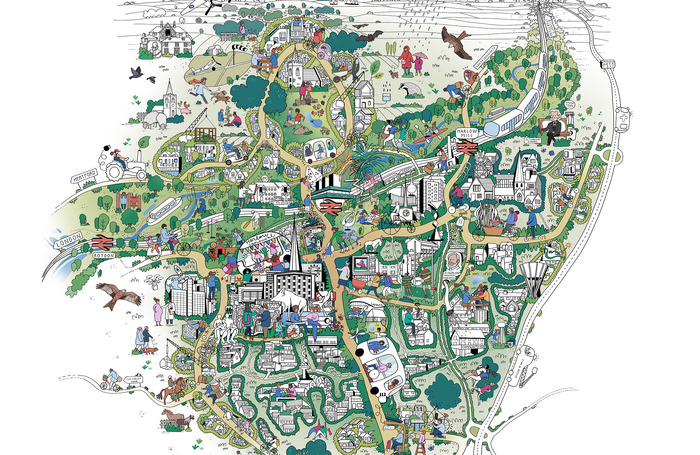

So when I took office as President of RIBA in 2017, we launched ‘Future Place’: a project aimed at addressing the issue of local authority capacity to help build better places. The programme offers the combined resources of an array of national organisations and institutes – RTPI, LGA, Historic England, Homes England and Local Partnerships, as well as RIBA – and focuses those resources to accelerate the transformation of places in partnership with local authorities and communities.

Shared learning from action research

The first round of Future Place supported five local authorities across the country. Working together with local stakeholders and architecture practices – as well as experts fielded by project partners – they developed forward-looking placemaking strategies to benefit local communities. That knowledge was since shared with the sector in various formats including a report, a series of case studies and a film.

As an action learning project, the long term goal of Future Place is to create a platform of knowledge, experience and skill on which local authorities and their partners can build their capacity over time. This is a win-win situation for all involved. Participating local authorities benefit from informed design input, the practices involved get to demonstrate and develop skill in stakeholder engagement and urbanism, while partners make an important contribution to placemaking across the country.

Planning for the future?

At the heart of Future Place sits the aspiration to put high quality design at the centre of the planning process. There clearly is an overlap, here, with the ambitions stated in the government white paper. This is positive, but the white paper runs up against the same issue that Future Place intends to address – the lack of resources and skill in Local Planning Authorities.

The reforms include provisions to address this: a national model design code that developers and local authorities can use as a template, and the allocation of resources to enable authorities to appoint a chief officer for design and placemaking. All this will help, but the task is immense. If it is to succeed and genuinely take into account the diversity of issues that impact successful placemaking – whether in the context of existing neighbourhoods or new developments – the government must draw on all resources currently available.

The wider landscape

With that in mind, it is hoped that the proposed new design body will encompass the wide range of organisations and initiatives that currently operate in this space – creating a broad church to stimulate appropriate and informed localism. In addition to Future Place, there are several organisations who can contribute to this effort, including Commonplace Digital, Design for Homes, Design South East, Public Practice and The Glass-House Community Led Design.

As he lays down his plans to tackle the task ahead, my challenge to Nicholas Boys Smith is to create an effective network to help deliver the government’s ambition. Empowering communities to ensure developments are built to local preferences is no easy feat and the new design body will not succeed unless the government fully engages with the existing world of urban design which has long shared this ambition.

About the author

Ben Derbyshire is Chair of HTA Design, Historic England Commissioner, and Immediate Past President of RIBA.