There are straightforward measures that architects can implement in their designs in order to reduce a building's carbon footprint.

Will South, a Passive House designer and a Director at Etude, recently outlined Five ways housing design can help the climate emergency. Here, South goes into detail about taking the next steps: putting such measures into practice.

A high standard of airtightness

Good builders can achieve a high standard of airtightness, and will often take pride in doing so. However, architects must give them a design that can work. Here is some basic guidance for designing airtight buildings:

- identify one layer in the construction that is the air barrier and keep this layer as simple as possible

- draw the airtightness layer in each construction and make sure it is marked on all section drawings, that each one joins to each other and there is a product for making the connection

- specify proprietary airtightness tapes

- insist your builder conducts a mid-construction leak-finding air test and attends the site to discuss detailing

Improving airtightness also improves robustness against moisture, improves the effectiveness of a ventilation strategy, helps fire safety, and significantly reduces noise transmission.

Ventilation with heat recovery

‘Build tight, ventilate right!’ urged Earle Perera of the Building Research Establishment in 1992. In UK homes, ventilation should be a two-pronged strategy: opening windows for purge ventilation and summer fresh air, and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) for the background ventilation the rest of the time.

A ducted mechanical system has tangible benefits: filtered fresh air to all rooms; removal of moisture from cooking, washing,and drying clothes; controllable ventilation rates; and heat recovery with a miraculous 85% efficiency. A well designed MVHR recovers heat five times more efficiently than even the best heat pump can generate it.

There is a skill to good domestic ventilation design. If in doubt, enlist someone with experience and keep it simple. Here are two essentials:

- the MVHR unit should be readily accessible and near an external wall or roof so that the ducts connecting to outside can be as short as possible; this affects the efficiency of the system

- leave plenty of room for ducts connecting to all rooms as the smaller the duct, the more noise the system will generate - flexible ducts, (the crinkly ones such as those that connect to a tumble drier) have no place in this system

Insulation

There is no substitute for a good depth of insulation. For housing this means a thickness of about 300mm that completely wraps the heated part of the building. It needs to be protected from moisture, unbridged by structure and secondary metalwork, and uninterrupted around all surfaces including the floor and walls below ground. This could double in depth where there is an opportunity, such as loft spaces.

To achieve this thickness, a simple building massing and simple construction is crucial. Junctions to roof terraces and overhangs are particularly difficult, and insulation depth needs to be included in the design at planning stage for them to work well.

Insulation practice needs to move from dropping a bit of foam into the cavity to a significant, properly designed function of the construction. Proven successful wall constructions have included: split stud timber frames with blown insulation; full-fill cavity masonry; external insulation outside concrete, steel or cross-laminated timber; and even rainscreen cladding using specialist non-metal brackets.

Triple glazing

‘Triple glazing’ is generally short hand for a step change in window thermal performance. An extra layer of glass at the best thermal performance that this can provide is a strong start. However, it is not all about the product: size and position of fenestration might have the single largest effect on the environmental performance of a design.

The more optimistic future climate models all anticipate new homes having triple glazing. Installing only double glazing locks in poor performance for the life of the window and is a massive missed opportunity. It puts further burden on retrofitting for existing properties.

For the client, the windows and doors are focal interactive points. Focusing on modest triple glazing and the higher quality frame systems that support it can be a good way of improving your client’s satisfaction with the finished product.

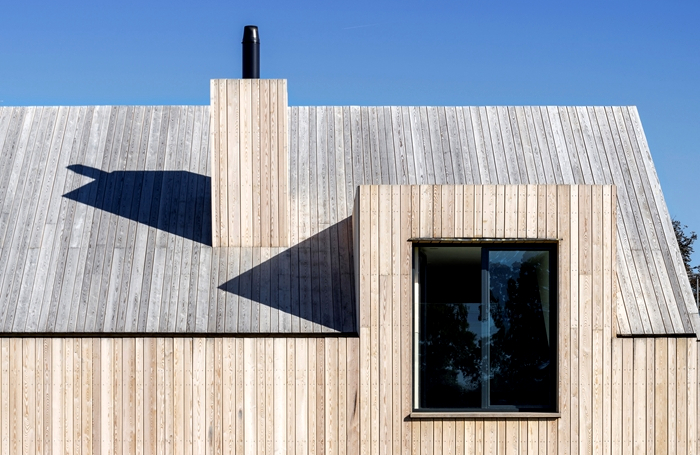

Timber frame first

The structure of a building is a core area for reduction of its overall carbon use: this is where the ‘timber first’ message comes from. Homes should be built from timber: it reduces industrial emissions and is one of our biggest opportunities for long-term carbon storage.

The challenge here is to rehabilitate timber as a high-quality construction material in an industry where it is often thought of as one of the cheapest ways to build, with a reputation for terrible acoustic performance.

But architects are practiced in problem solving, and in working with the opportunities and constraints of materials. They are more than capable of meeting this challenge and implementing timber frames successfully.

The RIBA’s Guerrilla Tactics conference will host a plenary event, Towards sustainable practice , featuring case studies of energy-efficient building from Tate Harmer, Architype and Arboreal; and a presentation on 'Embedding sustainability in everyday practice' by Craig Robertson of AHMM.

The event takes place on Wednesday 6 November 2019 at the RIBA, 66 Portland Place, London W1B 1AD. Tickets are now on sale.

Text by Will South, Director, Etude. This is a Guest Professional Feature edited by Neal Morris and the RIBA Practice team. Send us your feedback and ideas

RIBA Core Curriculum Topic: Design, construction and technology.

As part of the flexible RIBA CPD programme, Professional Features count as microlearning. See further information on the updated RIBA CPD Core Curriculum and on fulfilling your CPD requirements as an RIBA Chartered Member.

Posted on 29 August 2019.