It does not have to be an either or: designing buildings for healthy people or a thriving planet. As Elina Grigoriou points out, people’s wellbeing is integral to sustainability. The three pillars of sustainability, as advocated by the UN, are intended to represent the intersection of environmental, economic and social factors. As architects strive, though, to achieve challenging technical environmental targets in relation to the climate emergency, the quality of life of a building’s inhabitants can all too easily be overlooked.

So how might we set about developing design approaches that are more holistic? Interior designer and author of 'Wellbeing in Interiors: philosophy, design and value in practice' Elina Grigoriou will be speaking along with architect and author of 'Biomimicry in Architecture' Michael Pawlyn at RIBA Book Club on the topic of restorative design on Friday 26th June. Both design for people and the planet – albeit with very different starting points. For Grigoriou, design is determined by understanding how best to support the user’s wellbeing. For Pawlyn, designers should be looking to take their cue from nature’s systems, enabling ‘humankind to flourish’ through a shift from an ‘industrial age’ to an ‘ecological age’.

Why solutions for people lie in imitating nature’s functions

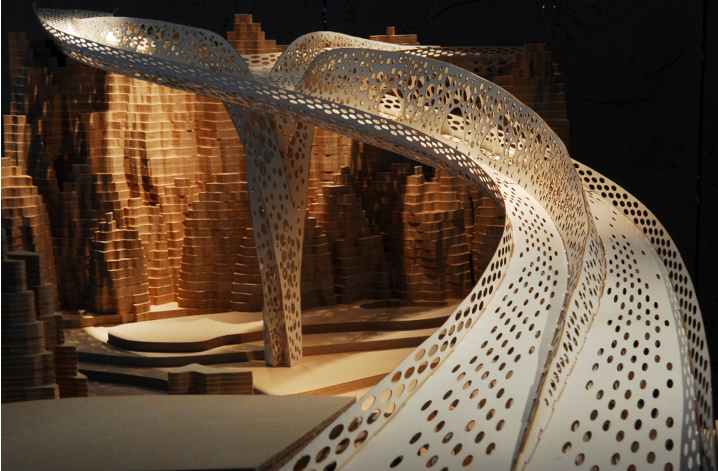

Biomimicry in architecture, as advocated by Pawlyn, is concerned with mimicking functional solutions found in nature – forms, systems and processes that have evolved over billions of years. This is distinct from biomorphic design that takes its inspiration from the shapes and forms of nature. Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, who closely studied birds to understand flight, can be regarded as a pioneer of biomimicry, whereas a medieval stone mason carving beautifully detailed leaves and birds into a column’s capital is biomorphic – drawing from nature as a decorative source for a building’s ornament.

When we meet, Pawlyn describes Biomimicry as: ‘a fresh perspective to familiar problems, providing a richer set of solutions than human ingenuity, which are solved in nature through an economy of means.’

The success of Pawlyn’s book, which is now in its second edition (2016) and remains a bestseller for RIBA Publishing, lies in the way that he has developed specific architectural solutions for a theoretical approach to design. Chapters are dedicated to: efficient structures, materials, zero-waste systems, water management, thermal control, light and energy use. Examples of modern built work are combined with photos and drawings of biological systems. In the first chapter, for instance, he illustrates how design has drawn from nature as ‘an accomplished maker’ of shells, domes, skeletons and webs with buildings by Pier Luigi Nervi, Frei Otto and Achim Menges. One of the most compelling and integrated large-scale projects to be featured is the Eden Project (2001). Given his expertise, perhaps it is no surprise that Pawlyn worked with Grimshaw for 10 years and was engaged on the delivery of this large-scale environmental project.

Pawlyn admits that, at present, the potential for the application of natural systems in architecture is largely untapped. We have only witnessed glimpses of it in contemporary work, where it is largely limited to the scale of the pavilion. The most significant advocates are Achim Menges at ICD University of Stuttgart, Philippe Block at ETH Zurich and the London-based practice Tonkin Liu.

The real possibilities for the project lie not at the building scale, but at the urban or even regional level, in which cities and their hinterlands become increasingly biodiverse and integrated within the wider natural ecology. Pawlyn evokes a seductively liveable image of an ‘atmosphere of a biomimetic city’ in which there is a ‘feeling of abundance: lush vegetation, fresh food, clean air and, at times, even an abundance of energy’.

In his book, Pawlyn concludes by summing up the meaning of biomimicry for people: ‘The substantial extent to which biomimicry could mitigate or avoid that scenario [catastrophic climate change] is perhaps the most significant connection between biomimicry and people’.

Designing for the whole person – body, mind and emotions

For Grigoriou, designing for human wellbeing has its foundations in the evidenced-based design approach of the healthcare sector that employs data and reason to develop design proposals. ‘Wellbeing’, though, reaches beyond the conventional definition of health – as a lack of illness – it aspires to provide not only a neutral state of being free from disease, but also comfort, resilience and emotional happiness. It caters for the spirit, as well as the physical body.

As ‘an experience, and not a design description’, a designer seeks to ‘support the wellbeing of occupants but not provide it’. For Grigoriou, ‘beauty’ and ‘comfort’ are prerequisites for human wellbeing.

The core tool for designing for wellbeing is the development of User Profiles. These enable the designer to ‘know in detail the measurements and preferences of the occupants’. This can require the creation of a number of different User Profiles to cater for distinct groups that use or inhabit any one building or parts of a building. These are worked up through occupant interviews at the client briefing stage. The design team play an important role throughout the design and delivery processes as the ‘gatekeepers’ of occupant wellbeing, ensuring all decision-making supports it.

Like Pawlyn, Grigoriou also believes that humanity needs to retain its connections to the natural environment to survive and then thrive. Biophilia is a persistent theme in Grigoriou’s book, as she highlights the importance of design features that enable people to retain their positive contact with the living world.

A quest for increasing knowledge

Despite their differing approaches, Pawlyn and Grigoriou are unified in their belief that successful holistic design, amid the climate emergency challenges, requires significant research and a widening of the curriculum in education. As Pawlyn pinpoints: ‘architectural discourse has a limited scope largely restricted to style, omitting economics and ecology.’ In order to advance evidence-based wellbeing, Grigoriou is currently undertaking a project with the University of Helsinki’s pedagogy research team, in an experiment that measures the impact of a classroom’s spatial planning and features of the interior on the productivity and welfare of students. What is apparent is that we are only at the very beginning of unravelling how natural life and humanity can be better served by the built environment.

Text by Helen Castle, Publishing Director at RIBA. With thanks to Elina Grigoriou and Michael Pawlyn.

Elina Grigoriou and Michael Pawlyn are talking at RIBA Book Club at 1.00 pm on Friday 26 June: ‘Can buildings be Restorative? Biomimicry and wellness in Architecture’

Elina Grigoriou, Wellbeing in Interiors: philosophy, design and value in practice

Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry in Architecture