Architecture is a brilliant topic for engaging and inspiring Special Education Need (SEN) students. Through RIBA’s National Schools Programme, we have witnessed how architecture naturally lends itself to providing meaningful and engaging learning experiences for some of the hardest to engage. This is because it creates opportunities to develop inclusive and graduated projects which are easily adaptable to an individual’s needs and preferences.

When talking about SEN students, it is important to remember that this term covers a vast range of needs and abilities, both physical and cognitive, and that every student is different with unique requirements. SEN students form around 14% of the population in schools (approximately 1.3 million students)[1]. Only 10% of these students go to special schools[2] (often those with severe learning disabilities) and the rest are placed in mainstream schools, which has advantages and challenges for both educators and pupils. Like all students, SEN students have personal strengths and weaknesses, and a good educator will plan projects that consider each individual’s needs, whilst creating a workshop all students can enjoy and participate in.

Architecture is a topic which organically stimulates different types of learners, as it covers everything from abstract and emotional thinking, to logical processes and precision planning. As a result, architecture will appeal to both creative individuals who like thinking about the big picture, as well as those who like to focus on detail and understand exactly how and why everything is as it is. A student who struggles with writing and reading skills but loves expressing ideas in a visual format will thrive on the more artistic elements of architecture, such as creating perspective drawings or spacial diagrams, whereas a student who finds comfort in rules and repetition may appreciate learning about Architecture Orders (like those in Ancient Greece), or using scale rulers and laser tools to create accurate plans. Developing a variety of architecture activities that appeals to these different learning styles is very easy due to architecture’s scientific and artistic foundations.

It is also a highly tactile and sensory topic. Exploring and designing spaces allows most of our senses to be used – from looking at beautiful buildings to examining the role of soundscapes and scents. They play a role in understanding design and space. For students who have reduced senses, or struggle with tasks involving fine motor skills, this allows them to analyse and explore buildings and spaces in different ways – you don’t have to rely on just listening and writing. Similarly, the feel of different materials or physically holding things like models can help develop understanding through touch. Feeling how strong a brick is or how light a material is can help students understand what parts of their design these materials would be suitable for, helping them to practice critical thinking and make connections.

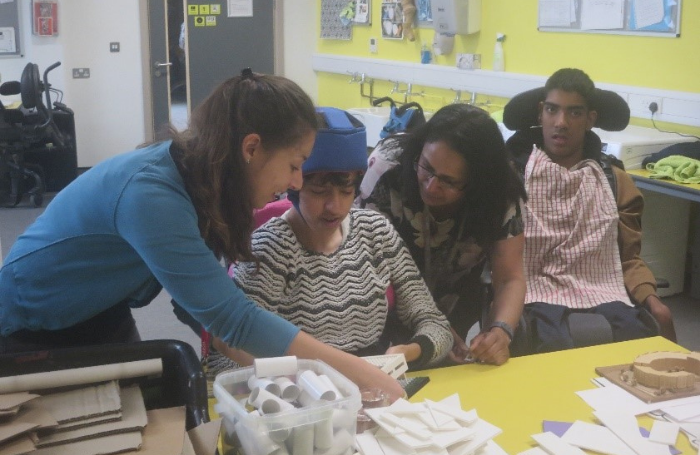

Common architectural tasks such as drawing, model making and communicating ideas can help develop crucial skills students may need to practice, whilst giving them alternatives if they struggle or grow impatient. In many of our workshops, we ask students to work together so that they can support each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and practice expected social behaviours such as listening to each other and learning to disagree with someone in a polite way. If collaboration becomes too difficult, it is also possible to assign certain tasks to individuals which come together at the end, and show how everyone has contributed (e.g. one student measures and cuts parts needed for a model, another decorates them and another cuts tape into appropriate sizes for students assembling things).

We have also found during our workshops that some SEN students often have specialist interests which architecture can complement and include. For example, one Year 8 student who was usually withdrawn in group settings took the lead in designing a bridge, as he took great pleasure in advising his classmates on the materials and dimensions they should consider (he read many books on transport and infrastructure). Similarly, a Year 5 student who loved historical timelines took great care and pride in producing detailed and accurate elevation drawings of Victorian houses, despite claiming to hate art. By linking architecture design briefs to students’ interests, or by allowing students to create their own design brief, architecture can cater to personal interests and hobbies which, as mentioned, can encourage students to try new things. For those who struggle with decision or independent thinking, you can still give them options – design a house which uses  colour or design a shop for something you like – meaning they can still link it to personal likes or interests, but less autonomy is required from the individual.

colour or design a shop for something you like – meaning they can still link it to personal likes or interests, but less autonomy is required from the individual.

Finally, as architecture can use many subjects and focuses on many skill sets, it is eas y to avoid things which may distress students or create triggers. Students who dislike messy materials such as clay and glue can opt for ‘clean’ materials, such as string and bamboo, and those who get overstimulated when meeting new people can be given time to do some private sketching or research. Using forest schools or exploring water in design can help incorporate sounds and environments that calm students and designing dens or safe spaces can help them communicate preferences and thoughts in a non-verbal format through omission or inclusion, making them feel more secure and in control.

y to avoid things which may distress students or create triggers. Students who dislike messy materials such as clay and glue can opt for ‘clean’ materials, such as string and bamboo, and those who get overstimulated when meeting new people can be given time to do some private sketching or research. Using forest schools or exploring water in design can help incorporate sounds and environments that calm students and designing dens or safe spaces can help them communicate preferences and thoughts in a non-verbal format through omission or inclusion, making them feel more secure and in control.

In conclusion, architecture is an extremely adaptable and versatile subject to use with SEN students, which can easily cater for individual interests and preferred learning styles. Real life architecture activities combine arts, science and communication, allowing educators to pick and adapt activities suitable for the group they are working with, while avoiding triggers that can hinder engagement.

As one of our Architecture Ambassadors, Andrew Simpson, stated, “Whilst there may be more to think about and prepare for with an SEN Workshop, we’d like to believe it is much more rewarding for it.”

References:

[1] Department for Education: Special Needs in England Report January 2019