An exhibition in the RIBA Library – Exposing the Barriers in Architecture from a FAME (Female Architects of Minority Ethnic) Perspective – visualises important messages that have emerged from a two-year research study. The study examines “how race and gender affect established practitioners, young scholars and students, from diverse backgrounds, knowledge and practices by engaging in conversations about the barriers in architecture and the built environment”.

The exhibition at 66 Portland Place in London is curated by FAME Collective, an activist group and research network founded to support women of diverse backgrounds and ethnicities. In this exhibition, the collective identifies the barriers currently in place that hinder women in architecture.

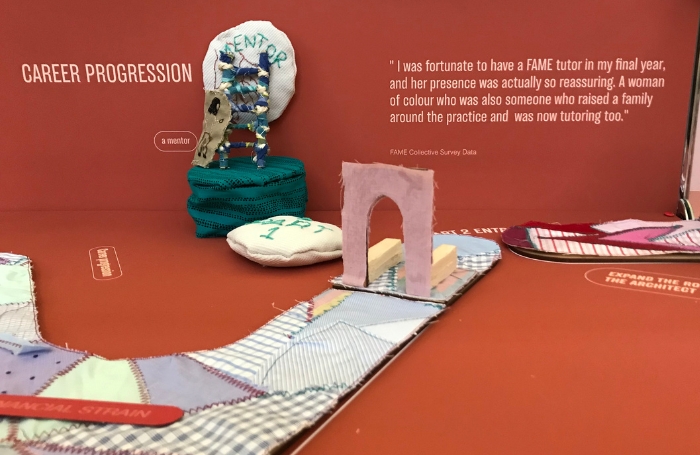

It does this by reframing barriers as gateways to success and sharing the lived experiences of women from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds who have succeeded in the profession and mapping how they did it.

Visualising the personal narratives of practitioners and students was no easy task, admits FAME founder and exhibition curator, Tumpa Husna Yasmin Fellows.

“We thought an exhibition would be a powerful way of sharing what we found, but it was a great challenge to come up with a creative form for the exhibits, particularly as we wanted to find a way to send a positive message,” she says.

What does the FAME Collective do?

FAME Collective was founded to support women of diverse backgrounds and ethnicities in architecture and the built environment with the aim of raising awareness of the inequalities and lack of diversity in the profession. Its two year research program, part-funded by the RIBA Research Fund, looked at the systems of discrimination that still affect individuals due to their race, gender and class.

“One of the things that came up over and over again in the research was that somebody's race or gender can hold them back in both studying architecture and in practice,” Tumpa explains. “These barriers are also about class and how much financial backing you have. Since my time of studying architecture more than a decade ago, things have changed dramatically and the profession is becoming less and less appealing to people without that financial support to enter architecture.”

She continues: “We think both education and practices need to be more accepting of other cultures. For instance, participants of the research who shared their live experience of barriers in architecture repeatedly mentioned the word ‘decolonising’ and how education needs to be ‘decolonised.’”

Tumpa uses an example of one of the students surveyed, who said that she had not been encouraged to review or conduct research into her own cultural heritage in architecture because her tutor was not equipped to help and guide her in that area.

What are the barriers FAME architects face?

While female students from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds are certainly becoming more visible in the early stages of architectural education, using the HESA Student Record 2018/19 as a reference, FAME Collective’s research reveals an attrition rate as they progress. “There are far fewer students from Asian and Black communities who go on to complete Part 3, for instance,” Tumpa says.

Tumpa says minoritised groups generally find it much harder than their white counterparts to find year-out jobs, frequently citing a lack of connections or anyone to recommend them as the reason.

Even when women from Asian, Black or minoritised ethnic groups find their way into practice, this area of research (referencing ARB’s Annual Report and Financial Statement 2020) concluded that white, male management culture is still the dominating demographic.

FAME Collective interviewed female architects who reported that even when they are recognised and capable of taking on projects, they are less likely to get the recognition that would automatically be given to a male counterpart; they are less likely to run meetings and less likely to be elevated by senior managers to the forefront of the team. There is also still a gender pay gap in practices.

Whatever their background, women then face the hurdles of taking time out to start a family and early years’ childcare that can hinder career progress.

“Our research has found that architecture is still a white, male-dominated industry,” Tumpa concludes. “There is a big problem with women dropping out even though they have come all this way to Part 3, investing so much time, finance and energy, but then they are lost, they just go missing.”

“Why this research is so important is that it highlights things that everyone can do to make a change because I think it is within all of us to address this lack of diversity and representation of not only women but also women of colour.”

What are the ways forward for architects?

On top of identifying the barriers, the FAME Collective makes six recommendations for change. Each one starts with the letter E:

1. Exchange

“We highly recommend that there should be a creation of a platform, whether it be in practice or in an institution where an open discussion and dialogue between people who feel that they're experiencing barriers and those who can make a change can take place. Perhaps people in power could invite people who are affected by barriers to join board meetings to make decisions and affect policies. For those who are affected by barriers, having a seat at the table where decisions are made is vital for overcoming discrimination in the profession.”

2. Empathy

“It is very important that the practice of compassion and empathy is applied. The barriers in architecture are experienced differently and in various contexts of home, university and office. Therefore, it is important to listen to individual voices, to empathise and to understand how the barriers in architecture can affect individuals and what support can be provided to navigate the pathways to success.”

3. Empower

“We really recommend that people from ethnic minorities - or people who are from any minoritised groups - join a network, such as FAME Collective, to be able to amplify their voices. Institutions or practices can then collaborate with these networks to empower and cultivate a diverse working practice and a wider profession that reflects the communities they serve.”

4. Educate

“Think about how we can expand the practice and pedagogy of architecture and expand how we teach architecture. We encourage learning from different cultural heritages because that's what represents the diverse demographic of our society and it should be reflected.”

5. Expand

“We should recognise that architects practice differently – some work with the community, or perhaps have a socially responsive way of practising.”

6. Enrich

“We feel that creating an inclusive and diverse profession actually enriches architecture. We really need to celebrate this diversity.”

The final research report Exposing the Barriers in Architecture from a FAME (Female Architects of Minority Ethnic) Perspective is available to download.

For this professional feature, we use the terms Black, Asian and ethnic minority, or white. RIBA recognises the limitations and challenges of using these terms, however, on this occasion they reflect FAME Collective’s important research and the language used therein. We will continue to develop our approach and are deeply committed to improving over time.

Thanks to Tumpa Husna Yasmin Fellows, Founder, FAME Collective

Text by Neal Morris. This is a Professional Feature edited by the RIBA Practice team. Send us your feedback and ideas.

Find out more about RIBA’s ongoing work in this area to ensure equity, diversity and inclusion.

RIBA Core Curriculum topic: Inclusive environments.

As part of the flexible RIBA CPD programme, professional features count as microlearning. See further information on the updated RIBA CPD core curriculum and on fulfilling your CPD requirements as a RIBA Chartered Member.