Although women held various roles in British architecture before the twentieth century, it was the First World War which brought women to the profession in substantial numbers.

Falling numbers of male applicants forced the Architectural Association to open its doors to women in 1917, to satisfy the need for new students. Campaigns by the suffrage movement resulted in policy changes, meaning architectural training started to be offered to women on the same terms as men.

Ahead of International Women's Day, we take a look at some of these early pioneers and the impact of their work on British Modernism.

Aiton & Scott

Norah Aiton (1904-1989) and Betty Scott (1903-1983) met as students at the Architectural Association during the mid-1920s. They practised together, initially gaining commissions from their families: a house for Betty’s parents and a significant commission from Norah’s father for offices for Aiton & Co in Derby.

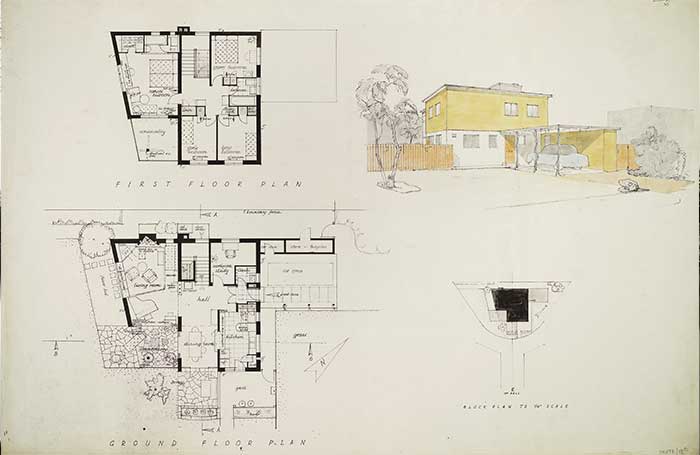

What they produced for Aiton & Co was the first industrial building of the Modern Movement in Britain. This unexecuted design for a house shows the elegance of their Modernism.

Elisabeth Scott

Elisabeth Scott’s 1927 competition design for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre marked the beginning of a breakthrough for women architects. Unanimously chosen by the assessors as the winning design, Scott proved that 'a girl architect' could win a prestigious large scale public commission, rather than be confined to small domestic projects.

After a year spent refining the design, her practice Scott, Chesterton & Shepherd completed the theatre in 1932. The building itself was well received in the architectural press who praised its honesty and ‘freshness of thought’.

Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, Scott Chesterton & Shepherd. RIBA Collections (RIBA2822-22)

Jane Drew

In 1933, Jane Drew was one of the founders of MARS – the Modern Architectural Research Group - formed to support architects working in the modernist movement. Drew’s work was integral to the introduction of Modernism into the UK.

Seeing the difficulties women in architecture faced, she opened an initially entirely female practice which took on large projects (including the Institute of Contemporary Arts), and focused on affordable housing in England, West Africa and Iran.

Whilst designing housing for the Festival of Britain, Drew was invited by the Indian Prime minister to design Chandigarh - the new capital of Punjab. Collaborating with Le Corbusier, Drew experimented with socially conscious housing strategies, and left a lasting impact on housing design across India.

Margaret Justin Blanco White

In 1931, M.Justin Blanco White was awarded a travelling scholarship and visited Austria, Russia and Germany and in the following year, undertook a study tour of France. She sat the RIBA final exam in July 1934.

She married in Cambridge in 1936, and designed housing in the city including the Shawms house - now Grade II* listed. During the Second World War, Justin Blanco White worked with Mary Crowley and Erno Goldfinger on proposals for housing, education and community projects.

She played a significant role in the research and development of planning policies for Scottish cities during the 1950s.

Jessica Albery

Jessica Albery (1908-1990) studied architecture at her mother's suggestion, who did not expect her to become ‘a serious professional’.

After five years of training at the AA, Albery spent six months on building sites in the City of London, observing buildings under construction, including Sir Edwin Cooper’s Royal Mail Office.

In the 1930s, she shared office space with other women who had set up on their own (Joyce Townsend and Judith Ledeboer). She designed and built five chalk pisé houses near Andover, using her on-site experience to supervise labourers and the foreman, before moving into the public sector, combining architecture and town planning on projects including Basildon New Town.

Drawing of a pair of proposed houses by Jessica Albery, RIBA Collections (RIBA99384)

Mary Medd (Crowley)

Mary Medd (1907–2005), believed in the social benefits of Modernist architecture.

She took a user-centred approach to school building, believing form and function should be complementary, and could enhance the school experience.

Medd was influenced by educational complexes in Scandinavia and America, where Modernist principles were believed to complement progressive education. Her designs for schools were typically light and airy single-storey, prefabricated units, which opened out to reveal play areas.

Model of Delf Hill Middle School by Mary Medd. RIBA Collections. (RIBA28520)